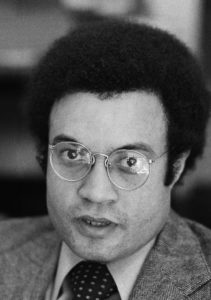

RPCV Drew Days III (Honduras) – first African American to head Justice Department Civil Rights Division dies

Drew S. Days III (Honduras 1967-69), who was the first African American to head the civil rights division of the Justice Department and later became solicitor general under President Bill Clinton, died on Sunday at a long-term care facility in East Haven, Connecticut. He was 79.

His wife, Ann Langdon-Days (Honduras 1967-69) said the cause was complications of dementia.

Born in the segregated South, Days went to Yale Law School, fought for civil rights through the courts and enjoyed a meteoric career that might have led to a seat on the U.S. Supreme Court if not for his legal opinion in an obscure child pornography case.

He knew from an early age that he wanted to work for civil rights. “I rode segregated buses and I was from the era with the segregated lunch counters and water fountains,” he recalled in a 2014 interview with the Touro Law Review. “I had a real feel for that. My mother was a schoolteacher, and she suffered from the fact that her aspirations were very limited because of segregation.”

He eschewed the traditional path of clerking for an important judge or networking at a corporate firm. Rather, he started out working against housing discrimination in Chicago with Martin Luther King Jr. and later joined the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, where he argued several school desegregation cases — including a lawsuit, which he won, to desegregate the same schools in Tampa, Florida, that he had attended as a boy.

President Jimmy Carter named him assistant attorney general for civil rights in 1977, making him the first Black person to head any division in the Justice Department. His tenure was marked by aggressive enforcement of the nation’s civil rights laws in cases involving police misconduct and discrimination in employment, housing, voting and education.

He joined the Yale law faculty in 1981 and remained there for 35 years. During that time he testified before Congress against the nomination of Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court, arguing that he lacked historical perspective on, and sensitivity to, matters of discrimination. While at Yale, Days also took a three-year detour at the relatively young age of 51 to serve as solicitor general, the nation’s top courtroom advocate.

He was widely perceived as destined for a seat on the federal bench and possibly the Supreme Court. But a political uproar early in his tenure in the Clinton administration made such an elevation unlikely.

The case involved the 1991 conviction of a Pennsylvania man, Stephen A. Knox, for possessing videotapes of minors involved in sexually explicit conduct. “Sexually explicit” had been defined by Congress as “lascivious exhibition of the genitals or pubic area.”

When Knox appealed his case to the Supreme Court, President George H.W. Bush’s Justice Department supported upholding the conviction. But three months into his new job, Days noted that the girls in Knox’s tapes were in fact clothed and were not acting lasciviously, and so in his view the tapes did not meet the law’s definition of sexually explicit.

His “confessed error” — a legal practice in which the solicitor general admits a lower court incorrectly decided a case — reversed the Bush administration’s position, and Days recommended that the case be sent back to the lower court. The Supreme Court did so, but eventually reaffirmed the conviction.

Once Days said the case had been wrongly decided, Republicans in Congress and their conservative allies pounced, accusing the new Clinton administration of being soft on crime and holding radical legal views.

The issue became so incendiary that Republicans denounced Days’ stance on the Senate floor. Democrats joined them, and the Senate voted unanimously to condemn Days’ interpretation of the law.

Clinton then sent a letter to Attorney General Janet Reno saying that he agreed with the Senate, and that child pornography laws should be interpreted as broadly as possible. A senior Clinton official told Newsweek at the time that the Knox case “cost Days a seat on the Supreme Court.”

The president similarly reversed other decisions by Days, who took the reversals with equanimity. “I did what I had to do, to the best of my ability and to my conviction,” he told Newsweek, “and the president exercised his authority.”

“Drew was committed to principle, not politics,” Harold Hongju Koh, a former dean of Yale Law School, said in a phone interview.

“It would have been easy for him to do the politically expedient thing to get ahead,” Koh added, “but that was not in his DNA.”

Drew Saunders Days III was born on Aug. 29, 1941, in Atlanta. His father, Drew Saunders Days 2nd, was an insurance executive and accountant. His mother, Dorothea (Jamerson) Days, was a schoolteacher.

He grew up in Tampa until the early 1950s, when his father landed an insurance job in New Rochelle, New York, and the family moved north.

He received his bachelor’s degree in English literature from Hamilton College in upstate New York in 1963 and his law degree from Yale in 1966.

Days had loved to sing — he practiced Renaissance madrigals in the shower — and, while at Yale, was a featured tenor in the Yale Russian Chorus. When the chorus sought out female singers for roles in the Glinka opera “A Life for the Czar,” Ann Ramsay Langdon, a student at Connecticut College, volunteered. The two got to know each other during rehearsals, and they married in 1966.

While at law school, Days worked for a civil rights lawyer in Georgia and afterward briefly joined a small firm in Chicago. He and his wife then served in the Peace Corps for two years in Honduras.

Days came to the attention of Carter when Carter appointed Griffin B. Bell as attorney general. Bell, who had sat on the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, had been impressed with Days when the young lawyer was arguing school desegregation cases in the South. Days headed the civil rights division for the duration of the Carter administration.

During his later stint as solicitor general, Days argued 17 cases before the Supreme Court and oversaw a group of lawyers who made more than 180 appearances.

One of his most noted cases was his successful argument against term limits for members of Congress. The 1995 decision, U.S. Term Limits v. Thornton, threw cold water on a popular movement, heralded by Newt Gingrich, the speaker of the House, in his Contract With America, that had nominal support from many politicians, but little real enthusiasm.

After serving as solicitor general, Days returned to Yale, where he hung a sign in his office saying, “No soliciting.” He continued to teach while practicing at a private firm, Morrison & Foerster, in Washington. He led the firm’s Supreme Court and appellate group from 1997 until his retirement in 2011. He retired from Yale in 2017.

In addition to his wife, he is survived by two daughters, Dr. Alison L. Days and Elizabeth J. Days; two granddaughters; and his sister, Jacquelyn D. Serwer.

Reflecting on his life in an interview with his daughter Elizabeth for StoryCorps in 2008, he said he had been pleased that when he moved his family to New Haven in the early 1980s, his daughters were taking the bus to public schools.

“I put perhaps a million kids on school buses” he said, referring to his involvement in school desegregation cases that led to mandatory busing. “To have my daughters take school buses voluntarily and enjoy it makes me feel better.”

No comments yet.

Add your comment