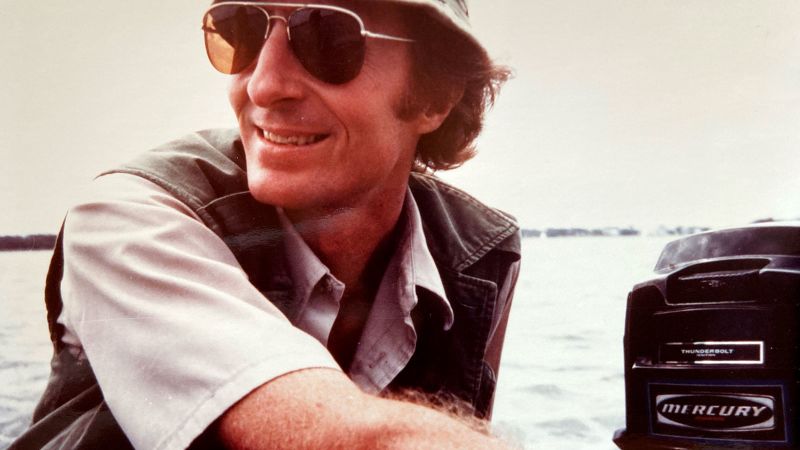

Remembering RPCV Gary Strieker (Swaziland)

Gary Strieker (Swaziland 1968-70) had every reason to be a pessimist. People dying of hunger, brutal killings and many other horrific events that he covered as an international reporter unfolded right before his eyes.

Yet Strieker never lost his optimistic spirit or his passion to shed light on critically important but often underreported stories on the environment and global health.

Strieker — who passed away in July of this year at age 78 — was CNN’s first Nairobi bureau chief, helping the network open its reporting hub in the Kenyan capital in 1985. Colleagues say he covered the entire African continent — sometimes as a one-man band — during the network’s early years when news gathering budgets were lean.

Strieker won an Emmy award in 1992 for his role in CNN’s coverage of Somalia’s civil war and he is credited with being one of the first television journalists to enter Rwanda as the genocide unfolded there in the spring of 1994.

He spent the latter part of his career focusing on global environmental issues — most recently producing “This American Land” which airs on PBS stations across the US.

This career shift came about in the mid-1990s after an encounter with Ted Turner, CNN’s founder, who shared Strieker’s passion about conservation and the environment.

“(Gary) had this idea he wanted to be CNN’s environmental reporter,” said Norgaard. “Every year or so we had (a) conference in Atlanta and I walked down there with Gary and I hear Ted yell, ‘Gary! Come sit here!’ and he announces to everyone, ‘Gary is our guy in Africa!’

“They sat down and started talking and then Gary just mentioned this idea to him about environmental (reporting) and I remember Ted turning around, looking at Tom Johnson (CNN’s president at the time) and going, ‘Tom, this is brilliant! I love it, let’s make it happen!”

Other colleagues who recalled the story said Johnson later half-jokingly swore never to sit a correspondent next to Turner again.

In 1997, Strieker and his second wife Christine moved to Atlanta where he worked as CNN’s global environment correspondent. His reporting on central Africa’s bushmeat crisis, as well as deforestation in Indonesia, Peru and Papua New Guinea, earned him the National Press Club’s top prize for environmental reporting in 2000.

“Gary was, in a lot of ways, ahead of his time — he was pushing for environmental reporting years before any other network,” Norgaard recalled.

Norgaard, CNN’s former Johannesburg bureau chief, was a junior editor on the network’s international desk in Atlanta when he first began working with Strieker.

“I was born and grew up in Africa, so we kind of had a special understanding,” he said.

Strieker was different than many international correspondents at the time who, Norgaard said, could be “really wound-up” and rude when they called the international desk.

“That was never him,” Norgaard said. “He was always calm, courteous … that’s what I will never forget about Gary. I didn’t know him that closely, but he’s someone you considered a friend.”

Born in the small Illinois town of Breese on July 7, 1944, Strieker grew up in San Diego, California – eventually earning a law degree from UC-Hastings in San Francisco. Strieker and his first wife, Phyllis, joined one of the first US Peace Corps teams in 1968 on a mission to the newly independent African Kingdom of Swaziland – now Eswatini.

Strieker spent five years in Swaziland serving as a legal advisor to the new sovereign government and helping draft a bill to protect Swazi land rights. During this time, his eldest daughter Lindsay was born. Strieker took a job with Citibank in Beirut in 1975 during the early days of the Lebanese civil war before returning to Africa as Citibank’s resident vice president for its regional office in Nairobi, Kenya.

Strieker’s twin daughters, Rachel and Alison, were born in Nairobi, and some health complications put Alison’s life at risk.

“The doctor at the hospital who was taking care of me was just very nonchalant and said, ‘Well … we’ll see if she makes it through the night,’” said Alison Strieker, recalling her dad’s story. “And my dad said, ‘Is there something we can do?’ and the doctor said ‘She needs blood for a transfusion.’”

Gary Strieker said he asked the nurses to test his blood type and he was a match. Years later, Alison said her dad saved her life a second time when he donated his kidney to her.

“He’s my favorite person on earth,” Alison Strieker said. “I still have his kidney to this day.”

As his daughters were growing up, they were the center of his life and he captured many moments of their young lives on a movie camera and an old Kodak “Brownie” camera.

His passion for photography sparked his pivot to journalism.

“The photography mainly got him interested in not just the images but telling a story … about people and places and animals that do not have a voice — and that seemed to be his real passion,” Alison Strieker recalled.

After a brief stint with ABC News, he joined CNN in the early 1980s, setting up the new network’s bureau in Nairobi and becoming its only correspondent on the African continent at the time.

“Gary entered the world of reporting in countries in Africa at a time in the 1980s when long-running conflicts in Ethiopia, Sudan, Somalia coincided with drought and famine (and) led to large refugee crises,” former CNN supervising editor Eli Flournoy recalled.

“Gary was there on the ground, year after year, covering, documenting, illustrating these endemic conflicts.”

Strieker had a lot of close calls during his reporting career.

“He was in crash landings in planes, he was in car accidents where other people died — he was just very dedicated,” his oldest daughter Lindsay Strieker said.

After a car accident in Rwanda, he was declared dead and taken to the morgue.

“He woke up in the morgue as a toe tag was being attached and said it damn near killed the medical worker when he sat up,” recalled Jim Clancy, former CNN anchor and international correspondent.

He had another brush with death while reporting on the 1995 Ebola outbreak in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of Congo, that left hundreds dead.

“Gary … fearlessly went in and covered the Ebola patients and the operations of the (Kikwit) hospital, which was one of the first of its kind to treat an infectious outbreak like Ebola,” Flournoy recalled. “It was a very, very dangerous environment.”

At one point, the local authorities began implementing a quarantine and approached Strieker, who they believed had been exposed to Ebola.

“They were going to put him in the hospital’s Ebola wing,” Flournoy said.

Equipped with a satellite phone, Strieker called the international desk in a panic.

“He (said) ‘We have to do something to prevent this from happening, because I will almost certainly die if I’m quarantined in this hospital,’” Flournoy said.

After a “mad scramble” which involved lots of phone calls and the intervention of United Nations officials, Strieker was allowed to leave the country instead.

“Gary continued to be unflappable, determined to get down to the facts of the story at the same time as being able to always find the human story within the larger conflict,” Flournoy said. “He was a remarkable storyteller.”

Strieker never lost his curiosity or energy for shining a light on critical stories about people who are impacted by global health and environmental crises.

“It was never about getting his face on TV or a higher Nielsen rating,” said Dave Timko who worked with Strieker on “This American Land.”

Strieker only cared about using his platforms to tell the stories of people across the world who were in need.

“Sometimes he’d say, ‘If I don’t go to those places, nobody’s doing those stories,’” his widow Christine Nkini Strieker said.

He was a devoted father to the couple’s two children Reid, 20, and Nandi, 16, sharing stories with them at dinnertime about his adventures and spending every moment he could with his family when he wasn’t on assignment.

Even when he became ill, Christine said that Strieker was determined to get better so he could start working again.

“He refused to say, I’m too sick to do anything,” she said.

After Strieker’s passing in July, friends and former colleagues flooded a shared Facebook page with memories — all recounting Strieker’s incredible stories, his quiet bravery in the midst of incredibly dangerous reporting assignments, his wit and genuine devotion to the craft of journalism.

“His message to us was, ‘Life, with its ups and downs, is an adventure – and it’s important to stay curious and compassionate,’” said his daughter Rachel.

It’s some comfort to the loved ones he leaves behind, including his five children and three surviving grandchildren, who are picking up the pieces after his passing.

“The more we don’t look at the sadness and the more we look at the positive in the life he gave us – that’s the thing I want my kids to carry on,” Christine Strieker said.

No comments yet.

Add your comment