One Day in Ethiopia

This is a letter I wrote when I was a PCV in Ethiopia. It was published in the collection Letters From The Peace Corps in 1964, selected and edited by Iris Luce. She wrote in her introduction to her book.

This is a letter I wrote when I was a PCV in Ethiopia. It was published in the collection Letters From The Peace Corps in 1964, selected and edited by Iris Luce. She wrote in her introduction to her book.

It was my good fortune one evening to be seated with the wife of Senator J. William Fulbright, whose daughter was working here in Washington at Peace Corps Headquarters. Mrs. Fulbright suggested that someone should compile a collection of letters from Peace Corps Volunteers in the field to give Americans a firsthand report on the triumphs and the hardships that these people have experienced while working in the Corps

“One Day in Ethiopia” was a letter I had written home to my family and friends, several at the agency in Washington that Iris Luce found and included. In her introduction to the chapter, “One Day in Ethiopia,” she wrote:

Rarely did a single letter from overseas capture the mood and the flavor of life in the Peace Corps as completely as this one from a volunteer serving in Ethiopia. Written by a young teacher, it is reprinted here in full.

Here is the letter….I wrote about being a PCV in 1962.

•

One Day in Ethiopia

by John Coyne (Ethiopia 1962-64)

In the morning now when we awake it is raining. Our roof, as most roofs in Addis, is tin and it is pleasant to wake at six to the heavy, amplified rain overhead. There are shutters on the two windows of my bedroom that keep it dark. It is cold, too, and in the mornings there is dew in the garden. The house is quiet. Today is Friday—my day to get up early and chop wood for the hot water heater.

My bedroom, like the other three, is big—twelve by twelve—with a high ceiling, a door out onto the front porch, wooden floor, dirty pale blue walls, and typical Peace Corps furniture. The mattress sags, as a hammock, in the bed; the wooden clothes closet has a warped door; the desk is small and shakes. I have constructed an artless but usable bookcase of stolen red bricks and unpainted planks; the walls are decorated with maps: Ethiopia, Africa, the world.

Chopping wood for the fire is a simple ten-minute task; I do not feel like Robert Front, however, and go at it dutifully. It is still raining and I work under a durable lean-to behind the house. My axe is a haphazard arrangement of wood and cast iron. We handle the weapon gingerly. The wood is eucalyptus. We buy it for 17 Ethiopian dollars a cord and stack it against a fence separating our house from the servant’s quarters. A few days ago a baby baboon wandered into our compound. He sits watching me, an oversize rat clinging to the frame of the lean-to. I flip a chunk of wood at him and he scurries away, up the frame that holds our water tanks, onto the brick wall of the French School compound. I pick up the two handfuls of wood and return to the house.

Once the fire has begun, the bathroom becomes the most pleasant room in the house: warm and quiet. I sit on the edge of our washtub relic and scan through a collection of papers and magazines that have settled, finally, in the john as fuel for the fire: old copies of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch; international editions of the N.Y. Times; the American Embassy News Bulletins; the Ethiopian Herald. Copies of the International Time we pass on to our students telling them to overlook the English, hoping they will gain some idea of what a free press is. Besides this there are copies of: You and the Peace Corps; Ethiopian Tourists Pamphlet; Suggestions for Teachers Abroad (published by the American Bible Society); and a set of student papers on ‘How I Spent the Christmas Vacation.’

“The water begins to boil; it simmers inside the tank. I go back to my room and pick up my shaving equipment to have the jump on the others. Alarms go off all over the house; they resound under the tin roof. Sam is the first up, coming sleepily into the john. Tall, thin and blond, wrapped up in a blue Chinese-pattern bathrobe and looking like someone left over from the Fitzgerald generation. He is usually very exuberant in the morning, but last night we were out late; he mumbles a good morning, stuffs laundry into the basket, and shuffles back to his room in his Japanese sandals.

Our houseboy comes into the house and hangs his coat behind the bathroom door; he bows slightly and says, tenayis tillin’ (hello) to me, then goes back across the dining room to the kitchen. We are without a cook at the present—our last walked out dramatically when we refused him a raise (the cook was paid $55 a month; the houseboy receives $35)-and our meals are a community effort. I finished up in the bathroom and go back to my room and dress. The whole house is up now. My bedroom is still dark; I open the shutters—one window overlooks the garden, the other the landlord’s house; then I dress. We wear ties to school in Ethiopia which is not the case, say, in Nigeria where Volunteers often dress in shorts and sandals to stand the humid climate. Addis Ababa it never gets much warmer than a summer day back home, and without the humidity. I then stuff a set of my 2E class exercise books into a TWA bag (used extensively by the Peace Corps Volunteers for carrying the students’ exercise books back and forth to class). Checking my schedule, I see this Friday I have only five classes. It’s an easy day. Dressed and with my school books packed, I head back to the kitchen.

Jim has already started the coffee so I pull the frying pan out, cut a slice of Kenya butter into it, and hunt up some eggs. We usually are able to buy twenty eggs for $1—out of this, four or five might be bad. I beak them into a cup before placing anything in the pan. Ernie, who is the only cook among the five of living together, crowds into the kitchen and I turn the job of cooking the eggs over to him and cut the bread.

It is almost 7:45 when we all settle down for breakfast. Our meals are usually turbulent arrangements. The conversation is disorganized, amusing, loose. Breakfasts, for some reason, tend to involve spontaneous singing. We have three singers in the house. Their tunes are mostly from shows, a primitive rhythm beat out on the tabletop. Lately it’s parodies: “How are Things in Dire Dawa?” or “Why, Oh, Why Did I Ever Leave Massawa!”

Classes start at 8:15 with flag raising and the morning prayer. My first period is free today so I linger over a third cup of coffee and leave the house at 8:30 when everyone else is gone and the houseboy is washing up the dishes. Outside our compound the Churchill Road traffic is busy with traffic and school kids attending the French School. The intersection on our corner is a favorite unloading place.

The kids are of all nationalities and range in age from seven to nineteen. The sidewalk conversation is also international, six-year-olds conversing in Amharic, French, English, German. I pass through the little kids, cross the street and start down the hill toward the Commercial School. The weather has warmed up, almost 70 now.

It is an eight-minute walk to school. On the way I’m bothered by twenty or so shoe-shine boys; a half-dozen boys selling The Ethiopian Herald, Time, Newsweek (they both sell for 75c a copy) The Ethiopian Voice; five or six beggars; a dozen taxis who slow down and call, “yet no?” (where is it?). At the bottom of the hill, I stop and check our box at the Post Office, then cross the street again, walk past the Haile Selassie Theatre, and up Smuts Street to the school.

The Commercial School is one of the three or four best schools in Ethiopia with five buildings, a large faculty, and 450 students. (The enrollment increased by two hundred in the last term when we took on students from Haile Selassie I School.) The three main buildings are grouped around a quadrangle, the fourth side is Smuts Street. Two smaller buildings are behind. The quadrangle is large and covered with stone; in the center is a small garden of flowers, the flag pole and a bust of the Emperor. The buildings that surround it are grey, three stories high, and made of large bricks. Commercial School, as all schools in Ethiopia, was a boarding school until recently (this year); the dormitories (two) were converted into class rooms and a library, and, as a result, we now have a faculty room. The English faculty, having the largest single unit, was given a separate room for itself, and, after signing in on a sheet posted at the door, I go back to my desk and correct themes until 9:10—second period.

The Commercial School — now college

My first two classes are with 2E. This is an experimental class. They are at a second-year level, but have had one less year of schooling. The hope is that if the experiment works, education can be cut to eleven years, which would enable the country to produce more students, quicker. There are twenty-two boys in the class and two girls. They stand when I walk in and say, ‘Tenayistillign,’I answer the same, they say ‘Indeminadderu?’ (How did you spend the night?) to which I answere ‘Dehna’ (Good, or very well). The class prefect has placed the yellow attendance card on my desk, and I count heads and sign it for him.

Today we’re working on paraphrase—a difficult lesson in any language. More precisely, I’m trying to explain how we change rhetorical questions into direct sentences. I write a section of a poem on the board: ‘But who hath seen her wave her hand?”/ Or as the casement seen her stand?/Or is she known in all the land,/ The Lady of Shalott?’

Then I write the paraphrase. The chalk is terrible, my hand is covered with dust. I slide out of my suit coat to keep it half-way lean and start again: ‘But no one has ever seen her standing at the window, waving her hand; and no one in that district knows anything of the Lady of Shalott.’

Hands begin going up. I call on Yohannes, who says he doesn’t understand. “What?” I ask him. “Anything about paraphrases,” he answers. So, I begin explaining everything. It is a double period, and by the end of the first hour I’m back again where I started. Back to the Lady of Shalott.

There are not quite as many empty faces, but yet they do not understand how questions can be converted into statements. I start another approach. “Do you understand the poem itself?” ‘No.’ ‘Do you have,’ I ask, ‘any poems in your language that ask a question but do not demand an answer?’ They sit and think for a moment and then two or three volunteer poems.

A few more faces light up. I turn to Ababayehu Asfaw, one of my best students. ‘Can you translate the Lady of Shallott into Amharic?” He can and the class understand. Another battle won.

At 10:35 I’m finished with third period and back in the staff room for tea—a fifteen-minute break. These morning tea breaks usually constitute our English staff meeting. Today’s discussion centers around how many official tests we should give third years. (Official tests are ones which count on the term grade.) This is easily solved and the topic turns to movies. Splendor in the Grass has just played and been thoroughly panned by the English set. Tom, the chairman of the English section, who is around twenty-seven, small, thin, and always looks undernourished, speaks slowly and precisely, working his words over so that they come out well formed.

“You know he’s got a good idea there, Kazan, but it’s full of this Hollywood crap. Take for example the bit about his father. Why the way they carry on it’s absolutely ridiculous! You know that’s a curious thing about American literature—that obsession with the domineering father.” Muriel speaks up.

She is sitting crouched up on the chair (her favorite position), an Edna St. Vincent Millay character whose voice is high and cockney. “It’s a bloody scream,” she begins. “I think you Americans have been actually drenched in father-complexes.” She is still sitting in her fontal position. Leaning over, she lights a Players 3 cigarette and sort of shuffles around on the top of the chair. “You can’t write a bloody novel in your country without some reference to a terrible father, an unhappy childhood, a case-history of maladjustment. It’s a bloody riot.”

Tom adds. “It wouldn’t be bad if they could write about it in decent English. The only people you have that write English are Mailer and Styron, and no one reads Styron.” The debate continues; I try to throw it all back in their faces and remarks about the Angry Young Men. They heartily agree, which leaves me at a loss; then the bell rings. Eleven o’clock.

I have the next two period off, so spend another hour correcting papers. A long and tedious task.

An hour is about all I can take so I walk out on the school compound and cross over to the woodshop. My students have been working on a bookcase and I’ve not been in to see them for three days; the bookcase looks as if it won’t hold a paperback. I start to tear it apart but the bell rings for sixth period, the last period of the morning. I have 3B for comprehension. It’s not a particularly bright class or interesting. Today they’re having a test, a simple one, but it takes all period, they read slowly and frequently consul the dictionary.

John Coyne & Ernie Fox (Ethiopia 62-64) at the Market in Addis Ababa: photo by Rowland Sherman

At one o’clock morning classes are finished and I start back up to the house. It is quite warm now and the walk back is trying at this elevation. In the distance, up the slope of the mountain, is the center of Addis. From the Commercial School to the mountain, is a three-thousand-foot elevation. The buildings are white about the clusters of eucalyptus trees. I stop at the Post Office Box and pick up the international edition of the New York Times.

At the house, Ernie and Jim have already put together a lunch of oxtail soup and tuna sandwiches. Table conversation is mostly about the morning classes, who might come in from the provinces, and what we will eat that night. The conversation is seldom serious, but Sam has received a letter from a friend who wants to know if the Peace Corps experience is more valid to life than college. We toss the point around academically, never reaching any conclusions, but agreeing that, in terms of understanding anything about the world, the Peace Corps is an ideal training ground and that it keeps people away from the artificial world of college. As Sam says, seeing people begging on the streets and walking the dirt roads with leprosy and elephantiasis makes one aware of what really is important.

The Lion of Judah, Addis Ababa

The meal is over at two; we leave the dishes for the houseboy, and I go back into the bedroom and stretch out for forty-five minutes. I’m teaching Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country this afternoon and am three chapters behind my students. I finish those chapters and turn to Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom, a book that I’ve been picking away at for three weeks. Laurence is all involved with the cutting up of the Yarmuk Valley Railway and it looks as if he will never get out of the desert alive; I actually am acutely feeling his frequent rounds with dysentery.

There are only two classes in the afternoon. I return to school as the three o’clock bell sounds and climb up to the second floor to room 3C. They are reading Paton’s book. I have this class ten times a week and enjoy it most of the time. Half of the class are girls, which is unusual, and three are the prettiest Ethiopian women I’ve seen.

Students are still straggling in; a permanent habit of theirs, so I walk back and sit down next to Kinjit Woldel-Rufael, a quiet princess of a girl. Her father is wealthy, as most of the girls’ parents are, employed in one of the ministries and the owner of several coffee plantations. She is impeccably dressed with her hair set and wearing dark glasses. Today she has on a pale blue dress with short sleeves and a low waist line.

“That’s a pretty dress, Konjit,” I say. She bows her head slightly.

“Thank you, sir.” Like most Ethiopian girls she speaks barely above a whisper.

“Did your mother buy it for you?”

She replies by inhaling quickly, which means ‘yes’ to the Ethiopians.

I imitate her and she laughs, “Why do you make fun of me?” she asks.

I reply that I’m not and do it again.

She then questions me for a few minutes in Amharic, testing my skill: What are you doing this weekend? Do you have a girl friend? Why don’t we go to the library and I can read instead of having English?”

To all of this I answer lamely in halting Amharic. The class is alive with students chattering in Amharic; I clap my hands to remind them this is English and return to the front of the room. The next forty minutes we pore slowly over a dozen pages, stopping frequently to explain a word, a phrase, the general meaning. The process has a way of destroying all the literature of Paton.

Eighth period I’m back with 2E for a debate. Ethiopians’ are inherent debaters and they take to it readily. Last period on Friday is devoted to debates; today’s topic is: ‘Is Life In The Country Better Than Life In The City?’

They could argue for weeks on this alone. A new chairman each week chooses the title and the participants. The debates are beneficial in that they force the students to think on their feet in English. Next week’s topic, the new chairman, Asegedech Bzuneh, states, will be: ‘Is It Better To Marry a Rich Girl Tan A Pretty Girl?” I can hardly wait.

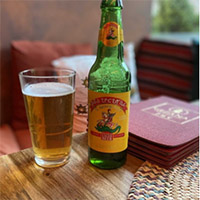

When the bell rings at 4:30 I go back into the faculty room and straighten out matters for the weekend, collect the papers that have to be corrected, fill out another questionnaire from the Ministry of Education (I wonder if anyone reads them?) and sign out. I walk back to the woodshop and wave to Sam who is out in the makeshift tennis court instructing three girls. In the woodshop l work with three students until six o’clock, then close up and walk over to the Ras Hotel for a beer with Jim. The sun has just about disappeared over the Debre Zeit mountains and clouds are moving slowly to the north over Mount Entoto. We’ll have rain tonight.

The Ras Bar is not elaborate, but it is quiet and there is usually an interesting group of tourists and businessman, passing through. It looks out on Churchill Street and the Caltex Gas Station. The Ted Shatto Safari’s landrover is parked in the driveway; a perfect name for a big game hunter. Ted himself is sitting at the bar, a short, heavyset man with a small goatee for a beard. He is talking about hunting Mountain Nyala and Walia Ibex with a German couple who have green Ethiopian flight bags slung over their shoulders.

Jim and I drink our St. George beer silently and listen.

The woman, who is pale and blond, keeps saying she wants a greater Africa Kudu. We leave them discussing rifles and go back up home. It is seven o’clock and dark; the street lights are on up Churchill.

Ernie is midway through preparing dinner and we give him a hand setting the table, cutting bread, making tea and coffee. Sam has located a cook through the American Embassy, so it looks as if their trouble will be off our hands. We settle down to dinner just as two girls from Debre Berhan come in; they have been without water for a week and want to know if they can use out bathroom for showers. We invite them for dinner and start the fire under the heater. By the time we finish dinner a dozen other province people have stopped in to use the phone or the john and to check out what is happening over the weekend. They all move on to the transient house where they’ll spend the night. Landrovers and jeeps move in and out of the backyard. There is a temporary power failure in the city and we take the candles into the front room.

At eight o’clock two Ethiopian friends of ours, Tekie and Samuel, drop I to see if anyone wants to go to the cinema. We make more tea and debate the questions; there are four shows in Addis and none start until 9:15. Sam has a date with an Italian girl he had just met; Merrill is going to play bridge at the Imperial Turf Club; Jim and Ernie have dates with Peace Corps girls to attend a German Bach concert next door at the French School. (As you can see, life is difficult in the Peace Corps.)

Teaching and afternoon beers have left me weary, so I turn them down with a promise that we’ll have them over within the week for injera and wat, the Ethiopian dinner.

Slowly the house settles down as the doors bang closed and everyone leaves; a few more telephone calls trying to track down province people. I gather the messages and place them on the marble mantel of the fireplace; in the morning they’ll all be back at the house on their way uptown to do shopping for the week.

Then I go out and chop wood for the fireplace and start a small fire. It has to be done carefully for the draft is bad. There are five sets of exercise books to correct for the weekend is long and I let them go. Picking up Lawrence again I settle down before the fire and get back to the desert. Lawrence has joined with Allenby to capture Maan, and outside in Addis it has begun to rain again on the tin roof.

Sounds familiar, even after all these years.

Good stuff, John. Took me right back.

But you left out The Sheba Club.

John,

Your letter provided a window to potential Volunteers through which they could imagine their own future participation, as in, ‘wow, I can do that, too’.

Nicely done!

Jeremiah Norris

What could be better than such a gift of a letter that keeps on giving in unanticipated references

60+ years since (and counting). Coyne a total writer in so many writing genres all this time now.

I love this letter and will reread it as long as my eyes can see. It’s a long letter covering so much.

Ed (Edward Mycue from Ghana One 1961 end of August)