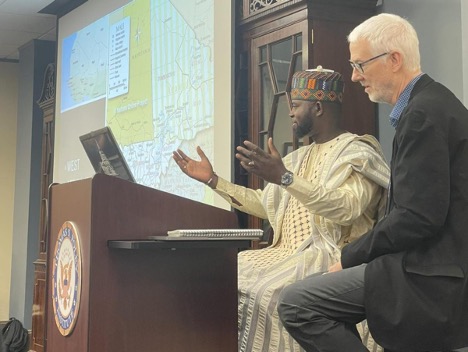

Founder of Timbuktu Center for Strategic Studies on the Sahel with Peter Chilson (Niger)

In the news

Foley Institute hears about effects of climate crisis overseas

El Hadj Djitteye and Peter Chilson discussing the effects of climate and migration in the West African Sahel

Founder of Timbuktu Center for Strategic Studies on the Sahel recounts experiences facing climate and migration crises

AIMEE SULIT, Evergreen reporter

October 4, 2023

Washington State University

English professor Peter Chilton (Niger 1985-87) shared that the United Nations High Commission for Refugees has found that almost 100,000 people try to leave Africa within West Africa every month and the population of displaced persons in places such as Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger reach about 3.2 million people at Tuesday’s Foley Talk.

El Hadj Djitteye, Timbuktu Center for Strategic Studies on the Sahel’s Founder and Executive Director also spoke and discussed the climate and migration crisis in the West African Sahel as well as the conflicts that result from them.

Djitteye gave his presentation alongside Chilson, who has been traveling to West Africa since 1985 and was a Peace Corps volunteer in Niger where he served as an English teacher.

Chilson recounted his Peace Corps experiences and described how he encountered numerous villages in places such as Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso whose populations had drastically gone down due to residents leaving the region.

“They were traveling South into countries like Nigeria, Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana to escape the drought and to look for work,” Chilson said. “The only alternative to them living in the Sahel was to starve to death.”

Chilson shared data from the United Nations High Commission for Refugees, which states that almost 100,000 people try to leave the continent within West Africa every month. He also said the population of displaced persons in places such as Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger reach about 3.2 million people.

“[They] are displaced by drought, climate change, also by resulting conflicts of those changes,” he said.

Djitteye said before founding the Center he had 12 years of experience in international development and peacekeeping and was working at the policy level at the UK Embassy in Mali. He used his knowledge of grassroots policy research and policy development to found the Center.

“[The think tank] uses community grassroots researchers that collect data on irregular migration, conflict dynamics, violent extremism and engage the youth and empower them to be peacemakers,” Djitteye said.

Since 2012, Islamist militants who have ties to Al Qaeda have occupied Mali’s northern regions, Djitteye said. In areas in Central Mali, climate change, drought and a lack of grazing land are all roots of conflict.

“Because of the impacts of climate change, there is no more grazing land for the herders to feed their animals,” Djitteye said. “So most of the time the herders’ animals go into the farmers’ land to get access to grazing land, so that creates a lot of conflict.”

One of Djitteye’s roles in managing this through the Center is to empower, work with, and negotiate with local community leaders, he said. They also aim to mediate the parties in conflict and find ways for them to coexist and create adaptation plans, he said.

Chilson and Djitteye said they took a trip this February through Al Qaeda territory across Central Mali and into Burkina Faso to foster peace negotiations. Both of them stressed the great danger and risks associated with a trip like this.

Djitteye said the majority of the fighters from the groups he encountered on his trip were very young and around 16-20 years old.

“As a young peacemaker, my goal is that if those young people should have basic social services, such as infrastructure and education, would their life be like this?” he said. “In the middle of nowhere with guns, trying to impose a new form of Islam which is more focused on radicalism on violence? It will never be the same.”

Djitteye described the reasons behind the actions of these terrorist groups, most of whom are from various Mali tribes and how they recruit people to their causes.

“One of the reasons they control that area is they use grievances like the lack of sharing of natural resources, equal opportunities and access to justice,” Djitteye said. “They use all those grievances to recruit the local population.”

Djitteye concluded by tying everything back to climate change.

“All [of it] can be blamed on climate change,” he said. “Climate change impacts the scarcity of resources and the scarcity of grazing land for the herders.”

About Peter Chilson

Peter Chilson (Niger 1985-87)

Peter Chilson (MFA Pennsylvania State University, 1994) teaches writing and literature. He is the author of the travelogue Riding the Demon: On the Road in West Africa (University of Georgia Press, 1999), which won the Associated Writing Programs Award in nonfiction, and the short fiction collection Disturbance-Loving Species: A Novella and Stories (Mariner Books, 2007), winner of the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference Bakeless Fiction Prize and the Peace Corps Writers’ Maria Thomas Fiction Prize.

Chilson went to West Africa in 1985 as a Peace Corps volunteer in Niger, near the border with Nigeria. A longtime visitor to Mali as a travel writer and journalist, he went back in 2012 for the Foreign Policy-Pulitzer Center Borderlands project. He was one of first western journalists to see firsthand the effects of civil war and the new breakaway jihadist state. Chilson’s e-book, We Never Knew Exactly Where: Dispatches From the Lost Country of Mali (Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting/Foreign Policy), came out in January 2013.

Chilson went to West Africa in 1985 as a Peace Corps volunteer in Niger, near the border with Nigeria. A longtime visitor to Mali as a travel writer and journalist, he went back in 2012 for the Foreign Policy-Pulitzer Center Borderlands project. He was one of first western journalists to see firsthand the effects of civil war and the new breakaway jihadist state. Chilson’s e-book, We Never Knew Exactly Where: Dispatches From the Lost Country of Mali (Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting/Foreign Policy), came out in January 2013.

No comments yet.

Add your comment