“An Example for Government” from Who’s Who in The Peace Corps

Sargent Shriver Writes

(Letter edited for length)

I hope this booklet—Who’s Who in The Peace Corps—will give Peace Corps Volunteers in the field a little information about the quality and the background of the members of the Washington staff.

I hope this booklet—Who’s Who in The Peace Corps—will give Peace Corps Volunteers in the field a little information about the quality and the background of the members of the Washington staff.

Nothing that I could say about the dedication and ability of these men and women could improve upon the assessment of them made by President Kennedy last June 14 when he said that they “have brought to government service a sense of morale and a sense of enthusiasm and, really, commitment, which has been absent from too many governmental agencies for too many years.”

He went on to say that he believes that the members of the Peace Corps/Washington staff “have set an example for government service which I hope will be infectious”.

Vital as these people are, however, not one of them is more important to the Peace Corps than the freshest, most apprehensive Volunteer in the field. Let that be clear. The Peace Corps is the Volunteers, but the Volunteers couldn’t be making their magnificent record without the dedicated support of the Washington staff.

Reading over their biographies now causes me to think back to the times when I first met them.

I had never heard of Warren Wiggins until I read a brilliant paper he had written on the idea of a Peace Corps. I read that paper at 2 a.m. one morning in the Mayflower Hotel when we were in the process of initial planning, and I immediately sent him a telegram, asking him to join our study group on an informal basis. Eventually he came to stay.

Bill Moyers came to me described as the ablest assistant Vice President Johnson had ever had in all of his years in Washington—and Bill was only 26.

Bill Josephson, at 27, had already achieved an enviable reputation as one of the shrewdest, hardest working young lawyers in I.C.A. Bill was an indispensable source of ideas. His careful legal work and boundless intellectual energy combined not only to keep us on the right track but to move us rapidly ahead, within, though, and sometimes around the bureaucracy of Washington.

Bill Haddad, at 34, was a prize winning investigative reporter for the New York Post who was so enthusiastic about the idea of a Peace Corps that he started coming down to Washington on his own time to help us in the early days. It soon became apparent that Bill was offering as much to the task as anyone, and I asked him to become a special assistant.

Pat Kennedy was a Woodrow Wilson scholar at the University of Wisconsin studying for his Ph.D. in history. His extracurricular work in the presidential campaign impressed everyone as energetic, imaginative, and dedicated. That’s what we wanted at Peace Corps headquarters. So we asked Pat to come in early too, and he proved to be one of those invaluable people who knows ow to go to work immediately never stops and gets a fine job done.

In one of the major, early decisions in Peace Corps history, I decided to try to get the U.S. Public Health Service to assume responsibility for the health of Peace Corps Volunteers around the world. The Surgeon General agreed to do so. More than that, he designated a brilliant physician administrator to my staff as Medical Director, Dr. Leo Gehrig.

Dr. Gehrig got us organized medically, drew up our medical policy papers, recruited excellent young doctors, and then was given two breath-taking career promotion by the Public Health Service—from Commander to Captain to Rear Admiral in fourteen months.

To my way of thinking, one of the best tests of the soundness and validity of the “Peace Corps Idea” as the high quality of the people who immediately came forward and expressed a desire to be part of it—to organize it, to serve it, and to serve in it.

When a brand new, untried untested organization is able to attract able and devoted workers like Charlie Nelson, Willie Warner, Sally Bowles, Charlie Peters, John Corcoran, Nan McEvoy, and John Alexander, it’s proof that you’ve got something fresh and challenging and worthwhile.

When that organization can continue to attract top flight personnel, you can feel a growing confidence. Paul Geren, Grant Venn, Sam Babbitt, Doug Kiker, Rogers Finch, Betty Harris, and Alice Gilbert all testify to the immense attraction of the Peace Corps idea.

It is this capacity—to attract, to challenge and to excite such people—that has made the Peace Corps what it is today.

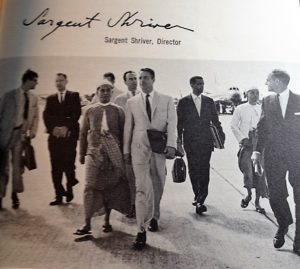

Sargent Shriver, Director

“I do not think it is altogether fair to say that I handed Sarge a lemon from which he made lemonade, but I do think that he was handed and you (The Peace Corps staff) were handed one of the most sensitive and difficult assignments which any administrative group in Washington have been given almost in this century.”

President Kennedy in a speech to the Peace Corps staff

This is nice John and I’ve glad you posted this. Ed

I got my fingers turning the “I’m” to “I’ve” AND noticing that I think Fall is for sure falling on me to smile.

And, we should not forget the origins of the concept of “Peace Corps Independence” — primarily from the foreign policy “establishment” of the times, and it’s operatives in the State Dept and USAID, which, for the most part viewed the new Peace Corps with skepticism. I remember that all too well. And then decades later a Washington insider and president of the NPCA tried to convince us all that PC Independence meant independence from the military. a total distortion, but it paid off for the perpetrator, with lofty career advancements. I hope everybody has read my earlier comments (Ghana. First Staffers) about those early days. John Turnbull Ghana-3 Geology and Nyasaland/Malawi-2 Geology Assignment.