A Writer Writes — “My Race Problem: Who Is A Patriot?” (Chad)

A Writer Writes

My Race Problem: Who Is A Patriot?

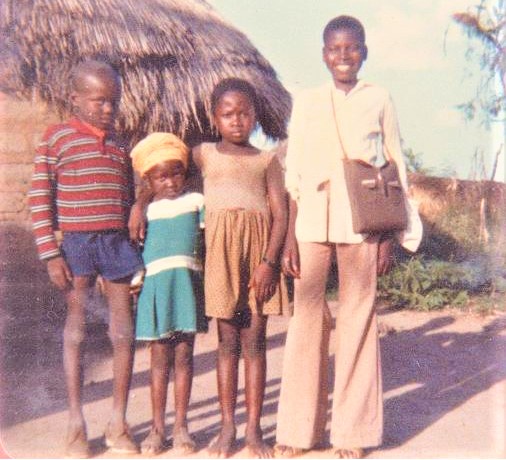

By Michael Varga (Chad 1977-79)

In 1976, the U.S. bicentennial year, I was cornered by my Aunt Martha. She had worked for the Pentagon in a variety of administrative  positions and believed strongly in serving our country. My eldest brother had been drafted during the Vietnam War and served in Southeast Asia for a 14-month tour. She was proud of his service but she was chagrined about what I was planning to do.

positions and believed strongly in serving our country. My eldest brother had been drafted during the Vietnam War and served in Southeast Asia for a 14-month tour. She was proud of his service but she was chagrined about what I was planning to do.

“Why can’t you teach in America?” she asked. She stood with arms akimbo and placed her hands on her hips.

“This is my opportunity to travel. To see something outside of Philadelphia,” I answered. In our Italian family, people spoke of the “evil eye,” a sort of death stare that translated as what you just said is not even worthy of a response. She gave me the full evil eye.

“Why do they have to learn English?”

“It’s where the Peace Corps is sending me. It’s the job they’re giving me.”

Aunt Martha had been a strong supporter of mine. She had sent me checks over the years as I completed my undergraduate degree as a secondary school English teacher. She had not had children of her own and as my aunt, she believed strongly in my role in the family as her loving nephew. She had envisioned my getting a job in one of the local high schools and remaining somewhere nearby. She imagined my being happy as a Philadelphian in Philadelphia. But by signing up to join the Peace Corps, I was upending everything she thought she knew about me.

“But I don’t get why you have to teach Negroes!” she wailed. She started to cry and I reached for her shoulder and hugged her. She continued to whimper and I held her tight.

The Peace Corps was sending me to Chad, Africa as a high school English teacher. I was leaving in a matter of weeks. She was making a final effort to dissuade me from following that plan.

“They’re Africans,” I said. “Yes, they’re black but that’s not important. What’s important is that the U.S. is committed to helping other nations develop. The Peace Corps is just one part of that effort.”

We were a lower class white family, living in a suburban Philadelphia neighborhood. There were no blacks in our neighborhood and we rarely saw anybody who didn’t look like us. My grandparents had come from Italy and Hungary at the beginning of the twentieth century and had achieved a better life for themselves in their new home, America. But they did not know anything about Negroes and kept their distance from them.

For me to be setting out as soon as I finished college to go to Africa was a shock to my family. My parents were quiet about it. They had watched my brother go off to Vietnam full of those worries about his losing his life in a war. But he was drafted so he wasn’t going by choice. I, however, was opting for this service abroad. Unlike my parents, Aunt Martha could not be quiet.

“Those African countries are full of wars. You’re going to be trapped as tribes kill each other,” Aunt Martha declared. She offered other reasons not to go (there’s leprosy; there are few hospitals; there’s dangerous animals, poisonous snakes, insufficient food). But I would not be swayed.

I had attended an urban high school in downtown Philadelphia and had made friends with a diverse student body. That included African-Americans, Asians, South Americans, and Mexicans. I was not bothered by heading to Africa where I would be the minority among the many African tribes. But for my family, for my white family, something was off about my “migrating” abroad to serve people of other races. My ancestors had come to America to seek a better life and they had found it. We weren’t rich so there was still a lot of work to do in stabilizing our finances. But the plan didn’t call for one of us reversing the “migration” and helping people in other countries to rise up, to better themselves.

Despite Aunt Martha’s tears, I went to Chad, had a fantastic experience, teaching, learning, growing. My family came to accept what I was doing (Aunt Martha regularly sent me CARE packages full of snacks and toiletries) and even established a pen pal relationship between my students and local American students. Everybody became better through this opening to another race, another people, another country, another continent.

That’s why I have a race problem with our President’s demeaning statements about the squad of Congresswomen, that they should “go back to where they came from.” Three of the four were born in the U.S. and no one—including President Trump—should be questioning their patriotism. A country that chants to send people back is not the America of my ancestors. Not the America of my family. Not the America I taught Chadians about.

We are better when we work to build bridges to others, no matter their color, their race, their location. We are united in aspiring toward a better life. Let us not define patriots by the color of their skin, but rather by how hard they work for the benefit of the nation.

•

After a stint — 1977–79 — in the Peace Corps in Chad, Michael Varga became an American diplomat serving primarily in the Middle East. He holds a Master’s degree in Economics from the University of Notre Dame and a Bachelor’s degree in English from Rider University. Michael is a playwright and actor, as well as a writer of fiction. His Peace Corps novel, Under Chad’s Spell, is available at Amazon. Three of his plays have been produced. “Collapsing Into Zimbabwe,” a short story, earned him first prize in the competition sponsored by the Toronto Star. His columns have appeared in many newspapers and journals. For other works by Michael Varga, visit his website at www.michaelvarga.com.

When I was leaving for Ethiopia in 1962, my father said to me: “Don’t come back with a polka-dotted baby.” I was astonished by this perverse joke because I didn’t consider him to be a racist. He was a West Point graduate, a colonel in the Army. But this was the America I lived in in 1962 (the country some would return to in order to make us “great” again.)

In 1996 I had an occasion to re-visit Ethiopia. I brought along my 21-year-old daughter, Amy, who volunteered to plant trees during her summer vacation. Walking with Amy down a big-city street a few days after our arrival, she stopped suddenly, saying: “Whoa, Dad! These people aren’t racists!” She was referring, of course, to passers-by with dark skins whom she realized carried none of the bigoted attitudes that we breathe in as Americans (whether we accept them or abhor them).

I thought to myself: “There’s progress, in just one generation.” I think that exposure and lived experiences are the answers to racism. Trump will be gone soon, along with America’s white majority. Amy’s daughter, Alma, is bilingual (English/Spanish). Hope is on the horizon.