Ellen Urbani (Guatemala 1991-93) Writes Modern Love Column For NYTIMES

ELLEN URBANI (Guatemala 1991-93) is the author of the Peace Corps memoir When I Was Elena (The Permanent Press, 2006), a Book Sense Notable selection documenting her life in Guatemala during the final years of that country’s civil war. She will publish in August, Landfall, a work of historical fiction set in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. Her autobiographical essays and short stories have appeared in a variety of bestselling pop-culture anthologies such as Chocolate for a Woman’s Heart.

ELLEN URBANI (Guatemala 1991-93) is the author of the Peace Corps memoir When I Was Elena (The Permanent Press, 2006), a Book Sense Notable selection documenting her life in Guatemala during the final years of that country’s civil war. She will publish in August, Landfall, a work of historical fiction set in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. Her autobiographical essays and short stories have appeared in a variety of bestselling pop-culture anthologies such as Chocolate for a Woman’s Heart.

She received a bachelor’s degree from the University of Alabama, and following the Peace Corps, she earned a master’s degree in art therapy from Maryhurst University, specializing in illness/trauma survival. Her work in this field was the subject of a short documentary, “Paint Me a Future,” which won the Juror’s Award at the Palm Springs International Film Festival in 2000, qualifying it for Oscar consideration. Ellen is considered an expert on the emotional repercussions of bio-terror and disaster, serving as a mental health specialist for the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and as an advisory board member at the Annenberg Center for Health Science Research. She has guest lectured at numerous colleges and universities and has taught writing at Portland Community College and the SUN School.

This piece appeared today, February 1, 2015, in The New York Times.

•

A Flower Delivery That Brought More Pain Than Pleasure

by Ellen Urbani (Guatemala 1991-93)

.

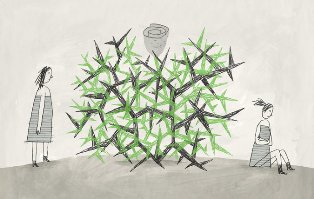

Brian Fea

With the best of intentions, I once did something regrettable.

I sent my younger sisters flowers.

The three of us have always been close. When we reunite at home, images of us in matching ballet tutus dance across the wall, our childhood selves reanimated via the grainy slides our parents project onto a tacked-up sheet in the living room. En pointe at the annual recital, arms raised, I graze my sisters’ shoulders with my fingers, conjoining us. We touch in nearly every picture.

In a flash of light, we are repositioned as Catholic schoolgirls, strolling hand in hand down the street. Another flash and we are younger still, the two of them riding me like a pack mule, chubby hands knotted in the mane of my hair, my red curls clashing with their straight brown locks.

Our hair was our primary distinguishing characteristic until I married young and spent my entire early adulthood with a man, whereas my sisters matured into middle age unattached but eager for romance.

I sent my sisters’ flowers to their workplaces.

My luckiest colleagues often received bouquets on birthdays and holidays, and I would flush with envy as passers-by stopped to inhale the scent of their good fortune.

I never got flowers. “Too expensive,” my husband would complain.

Settled for almost a decade into a not-quite-happy-enough relationship, I bemoaned the loss of allure that had wilted over time. “Come sit with me,” I’d coax from my perch on the sofa, but he’d smile and say he preferred his recliner on the other side of the room.

I craved touch. I craved attachment. I interloped in my sisters’ lives because there was no interloping going on in mine.

I sent the flowers with this unsigned note: “You make me crazy!”

For us, such anonymity wasn’t without precedent. When we all lived under one roof, we sometimes tossed each family member’s name into a dented metal mixing bowl and then extracted the name of our “secret pal” for the month, someone for whom we’d surreptitiously make gifts or hide special notes.

I sent my sisters flowers because I missed living a life where love visited me in such novel ways. I missed corny love notes and proof that I mattered. I missed surprise.

With narcissistic naïveté, I imagined my footloose sisters’ lives were packed with a passion mine lacked, and I fantasized about how it might feel for each to think she had a secret admirer – a butterflies-in-the-belly flutter that had long since faded for me.

I sent my sisters flowers without considering that my gift might cause more pain than pleasure.

The flowers went out midday, and I waited by the phone knowing my sisters would call each other, discover they both got the same arrangement with the same note, and realize the flowers came not from a stranger but from someone who loved them equally.

“Yes, it was me!” I would say when they called, and I’d have the fun of sharing in their surprise. Although the flowers did not come from lovers, who could complain when they had come with love?

But one sister awoke that morning with a cough and stayed home, unaware of the flowers at her workplace. By the time I realized the mishap and called to confess, the other sister had already brainstormed potential admirers with her colleagues, called the flower shop in a fruitless effort to uncover the identity of the sender, and contacted my mother who, knowing that a lock on my sister’s door had been broken recently, concurred the flowers must have been sent by a stalker.

No one but I connected the gift with the revival of an old family custom.

My first reaction on hearing of their criminal hypothesis was to laugh, but that’s only because I didn’t realize there are times it can be less painful to think someone wants to hurt you than to think someone fails to notice you at all.

My marriage hadn’t yet reached the point where my husband washed his dishes by holding them suspended above mine, scrubbing only those he used, ignoring mine, ignoring me. I wasn’t yet shushing my toddler and newborn all morning, brainstorming quiet pastimes so their father could sleep late as he was accustomed, undisturbed by our presence.

But invisibility has a shelf life. In our last year together, I was forever in his face, nit-picking, shaming myself with my efforts to engage him in battle. His anger scared me, but I roused it anyway, because negative attention was better than none.

“Stalker?” I asked my sister, amused by how swiftly my gesture had gone awry and perplexed by the rage she directed at me. I took offense to her insistence that I had singled her out for mockery, because I hadn’t any clue what it felt like to be alone. To watch the world, paired off, somewhere beyond your reach. To want to be enough for yourself, by yourself, while also struggling with the lonely reality of an empty chair across the table, the holiday dinner for one, the vacant space in the bed where the silence damns you with this: You may be good enough for yourself, but you’re still not good enough for anyone else.

My sister and I fought viciously over the flowers. She called me cruel and accused me of making a fool of her in front of everyone she knows.

“They’re just flowers!” I insisted. “Why can’t you accept that, however poor my judgment, I meant to do something to make you happy?”

“They’re not just flowers!” she countered, asserting they were symbols of my callous disregard for her loneliness.

Receivers smashed down upon their cradles, and the line between us remained disconnected for a long time. Not irreparably so, but still it was strange. We were the sisters who, as children, had our own secret words with which we communicated. How could we now have no common ground or language?

It wasn’t an estrangement, but an uncommon pause. Step by step, we worked hard to re-establish the connection. Dainty conversations full of forethought, alert for miscues. Short visits with predetermined agendas and whispered entreaties to our other relatives: “Whatever happens, don’t mention ‘Flowergate.’ “

Fortunately, with time, life’s natural ebbs engendered empathy. My sister fell in love and learned partnership is no picnic. I divorced and felt the raw ache of vulnerability. In that process, she once again became my stalwart, and when I needed her most, she came rushing fully back to my side. As I did for her.

I stood beside her on her wedding day.

Out in the pews, every extended family member clutched a flower, plucked from his or her own garden that morning as a symbol of love and support for the couple. I had been tasked with gathering the blooms into my sister’s bridal bouquet in the time it would take the soloist to perform a single song.

Blossoms in hand, I dashed into the wings, so absorbed by the challenge that I didn’t notice, until I pricked my finger, that the lower half of one rose stem bristled with dozens of razor-sharp thorns.

I couldn’t just leave it out; it represented someone’s love. Instead, I tried to snap the stem in half, desperate to separate what was beautiful from what was not, but the fibrous shoot only flexed and frayed.

Prodded by the concluding refrain of the song, I did the only thing I could: I turned my back and bit into the stem, severing it with my teeth and spitting the offending end onto the ground. It pierced my lip, but I licked the blood away and strode toward the altar with my sister’s bouquet.

Only then did I realize this was the first time I was giving her flowers since the ones that had torn us apart. She smiled as I walked toward her, tearful with happiness.

It made me remember her tears on that long-ago day, and her questions: “Why did you send the flowers anonymously, and with a teaser? Why couldn’t you have just sent the flowers with a note saying ‘I love you’ signed by you?”

I could have, of course. I should have. But where once I erred, I finally amended: I put my signature on this day.

I resumed my place at her side and passed the bouquet into the hand she then extended to her husband in hope and joy and anticipation. Who can say what will come of their union? I wish for them the happily-ever-after, but I also know, from experience, how love can wither.

I couldn’t intervene to give my sister something I wasn’t able to create for myself, but I did all I could for her on her wedding day. I bled while removing the barbs, in an effort to ensure her an unblemished beginning.

These flowers wouldn’t hurt her. I had taken the thorns.

•

A version of this article appears in print on February 1, 2015, on page ST6 of the New York edition with the headline: The Flower Petals Landed With a Thud.

Ellen Urbani is a writer in Portland, Ore. Her first novel, “Landfall,” will appear in August.

A thoughtful consideration of how the best intentions often may go awry between siblings. Nice use of flowers as symbols of something literal and something figurative of the seasons in any close relationship. Loved what the author apparently learned about loneliness and empathy. A well-written treatment of something that speaks to the sibling in each of us.