Tom Miller on Moritz Thomsen (Ecuador 1965-67)

Tom Miller has been writing about Latin America and the American Southwest for more than thirty years, bringing us extraordinary stories of ordinary people. His highly acclaimed adventure books include “The Panama Hat Trail” about South America, “On the Border,” an account of his travels along the U.S.-Mexico frontier, “Trading With the Enemy,” which takes readers on his journeys through Cuba, and, about the American Southwest, “Revenge of the Saguaro” (formerly “Jack Ruby’s Kitchen Sink” — which won the coveted Lowell Thomas Award for Best Travel Book of the Year in 2001). He has edited three compilations, “Travelers’ Tales Cuba,” “Writing on the Edge: A Borderlands Reader,” and “How I Learned English.” Additionally, he was a major contributor to the four-volume “Encyclopedia Latina.”

This following piece on Moritz Thomsen ran in the Washington Post Book Section in October 2008. Recently the article way expanded and republished in Spanish and English in Fronterad Revista Digital. It is republished with Tom’s permission.

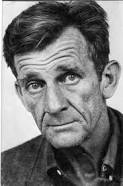

Moritz Thomsen, a reporter

by Tom Miller

He came to my Quito residence for dinner that equatorial night in 1982 wearing blue jeans and a recently washed button-down work shirt. I had delayed meeting the amiable white-haired Moritz Thomsen until I’d finished reading Living Poor (1969) and The Farm on the River of Emeralds (1978) , two books that had established his reputation.

By that time, he had achieved a low-key expatriate celebrity for his writing, for his impoverished life in a miserable fishing village on South America’s Pacific coast and for his cameo role in Paul Theroux’s The Old Patagonian Express. He became a stop on the literary gringo trail, lending support to aspiring writers — especially those who, like him, had served in the Peace Corps — and he was eager to learn the latest about the New York literary scene from published authors. I took to Thomsen, then 67 years old, immediately.

Moritz Thomsen (1915-1991) came from an extremely wealthy Seattle family and considered his father an “outrageous catastrophe” on a par with World War II. In the mid-1960s, toiling as a somewhat eccentric central California pig farmer, Thomsen enlisted in the Peace Corps and ended up in Rioverde, Ecuador, a village in a region whose meager economy was based on the day’s catch from the Pacific Ocean or crops hacked out from the adjoining jungle. He described his life in occasional pieces for the San Francisco Chronicle and eventually wrote a book about Rioverde and the Peace Corps. Most of his local Peace Corps work — his efforts to establish co-op stores, find a more practical way to raise chickens and pigs, set up community organizations and the like — floundered, but one family, the Prados, responded avidly to his precepts. After he left the Peace Corps, Thomsen and the Prados bought a nearby farm and set about living there.

His first two books set out elegantly phrased but brutal truths about life among the poor. Drawing on Proust, Stravinsky and Hemingway, Thomsen got inside the skins of his rawboned neighbors and found them burdened with a combination of passion and ignorance.

He was a man of almost insufferable integrity and undeniable charm. He deflected efforts to have his works translated into Spanish because, as he once confided, he did not want those he lived among to see what he wrote about them.

The Ecuadorian intellectual class didn’t know what to make of this foreigner who championed people they didn’t particularly want to acknowledge, whose published works about their country were well received in the First World and who didn’t thrive on the polite dinner circuit in Quito or Guayaquil. They were not ready for revelations or confessions. Previous foreigners who had written about Ecuador — Charles Darwin, Ben Hecht, Ludwig Bemelmans, Henri Michaux — never dug as deep as Thomsen nor truly unpacked and stayed, as he did for the rest of his life. Ecuador and its literary salons pretty much ignored one of the great American ex-pat authors of the 20th century.

Through the years, Ecuador has heralded its own writers, whose international notoriety often reflected global literary trends. Perhaps its best known 20th-century author was Jorge Icaza, whose Huasipungo (1934) describes life among indentured laborers of the Andean highlands. At mid-century and beyond, Nelson Estupiñán Bass, from the same region where Thomsen lived, represented Ecuador in Pan-African literature with his plays and poetry. Jorge Enrique Adoum, a poet and translator who was once private secretary to Pablo Neruda, is considered Ecuador’s representative among the boom generation writers. When women’s literature began to emerge in Ecuador in the 1970s and ’80s, novelist Alicia Yánez Cossio, now almost 80, was a leading voice. Most recently, Leonardo Valencia, a novelist from Guayaquil now living in Spain, and Gabriela Alemán, a Quito author, represented their homeland as part of the 2007 Hay Festival’s much-ballyhooed gathering of “39 Latin American writers age 39 or under,”held in Bogotá. Alemán’s recently published sixth book, the half-comic, halfheartbreaking Poso Wells, opens near Guayaquil with a politician’s sudden death by electrocution when he touches a microphone after having wet his pants.

It is Alemán’s generation of young Ecuadorian writers that has reappraised Moritz Thomsen and found his works worthy of rediscovery and celebration. They recently staged the First International Conference on Moritz Thomsen in Quito. The salient questions were these: Was Thomsen an ex-pat or a true Ecuadorian? Should his work be considered travel literature? What of his pre-Ecuador journalism in small-town California newspapers? And last, but not least, were we all engaging in hagiography?

At its peak, the conference filled large tables in Quito restaurants with foreigners and locals energized by Thomsen memories, analysis and pending posthumous works. (A hitherto-unpublished manuscript, Bad News From a Black Coast, is said to be forthcoming, and his first two books are finally being translated into Spanish in Ecuador.) The city of Quito posthumously made him an honorary citizen, with a street eventually to be named in his memory. It was a vibrant gathering, full of Pan-American literary chatter and long-lost friends. Some of us visited Libri Mundi, the well-stocked international bookstore Thomsen helped found, which has spawned branches throughout the country.

Not coincidentally, no one from Guayaquil, the far larger, industrial metropolis on the Pacific side of the country, participated. The rivalry between the Andes and the coast, which plays out in politics, sports, business and entertainment, extends to literary attitudes, too. Icaza’s international classic Huasipungo, for example, is not “the kind of literature I respect from Ecuadorian writers,” a Guayaquil editor sniffed. “Too much politics and social awareness, but very little artistic sensibility.”

Regardless of where literary opinions come from in this small but intense country, Ecuador doesn’t have many real readers. A thousand copies is a common print run for a trade book. Although Ecuador claims a 90-percent literacy rate among its nearly 14 million inhabitants, many have only functional reading skills. Depending on whether you’re in the jungle, the highlands or on the coast, the written word as art may not have much value.

Further, many of the country’s indigenous languages have an extensive oral tradition but a narrow written one.

When I lived in Ecuador in the early 1980s researching a book, I saw the chain-smoking Thomsen with some frequency and formed a deep friendship that continued in extensive correspondence. When I saw him last, he was living near the Esmeraldas River, his emphysema worsening, in what was, essentially, a tree house with a typewriter, books, a phonograph and classical records. We sensed it would be our last face-to-face visit, though neither of us said so. A few years later, he moved to Guayaquil for its sea-level altitude, choosing to live out his life alone, writing determinedly in a small apartment where, in the summer of 1991, he died of cholera, the poor man’s disease.

Thanks for sharing this piece by and about two writers I highly respect. I had the good fortune to track down Thomsen in summer 1989 when he was sequestered away in his tiny flat in a run-down Guayaquil neighborhood. Following that first meeting, we shared several extended conversations about his writing and his reading. Some time in the 1990s Miller and I exchanged phone conversations while he was researching a book; he introduced me to his memorable “The Panama Hat Trail.” Both writers have made a difference in my life and in my appreciation for literature. Finding one of them writing about the other makes me smile.

What wonderful encounters! You should write a book, Pat,

Tad Baldwin, Ecuador,1963 – 65 says

What a nice summary of Moritz’s life and work. Living Poor is my favorite Peace Corps book. I met Moritz briefly in Quito but don’t pretend to have any special insights. Tom Miller I also met during what I remember as PC Reunion activities here in Washington and his Hat Trail book is a fun read.

My brother suggested I might like this web site.

He was totally right. This publish actually made my day. You cann’t believe

just how much time I had spent for this information! Thanks!