Review: ELEPHANT CAKE WALK by Andrew Oerke (Africa staff)

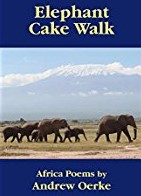

Elephant Cake Walk (Africa Poems)

by Andrew Oerke ( (PCstaff: Tanzania, Uganda, Malawi, Jamaica 1966-71)

Poets’ Choice Publishing, 2017

94 pages

$19.95 (paperback)

Reviewed by Ann Neelon (Senegal 1978-79)

•

I distinctly remember coming home from work especially dispirited one day 15 or so years ago. As a newly minted associate professor, I was in my “winning tenure, losing the thrill” phase, to quote a headline from The New York Times that stuck with me at the time. Strangely, I began to hear something resembling African percussion as I extricated myself from the car. I glanced up into our maple tree. There were our two young sons, perched in its branches, sporting an eclectic mix of Senegalese, Ivoirian and Moroccan costume elements from the Peace Corps boxes in our attic, including pointed “el hadji” shoes (which must have substantially ramped up the difficulty of the climb). Somehow, our sons had also managed to drag my husband’s balaphon up into the tree with them, and they were striking it, oblivious to the deleterious impact of its two broken gourds on its musical quality. Instantly, I was out of my funk.

I experienced a similar African-inspired leaping up of the heart in reading Andrew Oerke’s Elephant Cake Walk. Frankly, this volume of selected poems did not prove to be anything like what I was expecting. I guess by that I mean that so much poetry (witness, say, The Norton Anthology) is essentially elegiac, and these poems assertively aren’t. It so happens that the title poem initiates the volume. By the end of its first stanza, I had put aside my metastasizing fears that we have arrived at the tumultuous end of democratic days in America. I was instead delirious with Oerke’s joy in celebrating the onset of the rainy season in Botswana’s Okawango Delta. Hyperbole carries the day. After converting to Yoga, the dry season stands on its head, but “with Christian agape” baptizes all the nearly dead elephants. A miracle ensues: “Now the waterhole’s dustbowl is bathtub gin/drunken beasts gulp n gallop around in.”

Elephant Cake Walk testifies to a truth that nearly everyone has forgotten, namely that reading poems written primarily for adults, not children, can be fun. Poem after poem in this volume—veering off into metaphors inspired by subjects ranging from jazz to physics to Plato’s cave–constitutes a comic romp. Ogden Nash is most definitely somewhere in the background, as Oerke’s Nash spoof at the end of BUG OFF! Lake Malawi” bears out:

Buzz off! Shoo, fly, shoo.

Spring is sprung, the grass is riz,

I wonder where my flyswatter is.

This is a book of poems that non-literati can heartily appreciate. Its exuberance of language is contagious. How can you possibly go wrong with a poem entitled “Baboon Vavoom,” especially when it poses such a poignant question as

how much of me is him; how much of him

is still me?

It may seem, well, almost sacrilegious, to utter the name of Gerard Manley Hopkins in the same breath as Ogden Nash’s, but I do see Hopkins as a reference point for Oerke too. Hopkins of course committed himself to the poetic project of reviving in modern English the exquisite consonance and assonance of Anglo-Saxon verse. Oerke’s sound texture is rich, as phrases like “shadow’s shuck” (from “Second African Stiltdancer”) attest. Oerke’s obsessiveness might make for an even better connection with Hopkins, though. While Hopkins—a Jesuit priest who tried to suppress his poetic vocation because he believed it to be in conflict with his religious vocation—was God-obsessed, Oerke is Africa-obsessed. In daring to love Africa so ferociously, he takes some of the same risks Hopkins took in loving God. When he asks, “Was African dusk the photo filter photosynthesizing /the meta-bionic, distributive fuel we call “soul”?”—as he does in “The Sun Kingdom, Abu Simbel”—he is not all that far away from Hopkins’ saying, “The world is charged with the grandeur of God./ It will flame out, like shining from shook foil.”

Those who are conditioned to see African creatures from Sir David Attenborough’s perspective in BBC natural history documentaries such as Life on Earth, The Living Planet, etc. will be in for a (good) shock. Oerke’s love for wildebeests, ostriches, giraffes, etc., does not manifest in highbrow ways in the least. Tonally speaking, I was reminded of the mocking yet loving spirit of the impromptu tradeoffs my Catholic house helper and Islamic guardien used to have in my Peace Corps Senegal days, with Rose frenetically imitating Mame Diaga bowing to Mecca, and Mame Diaga equally frenetically imitating Rose making the sign of the cross. Photos by Cynthia Moss of the Amboselei Elephant Trust and by others working to save African animals from the brink of extinction add splendor to the volume. It is noteworthy, too, that Oerke includes humans in “The Game Park” section of the book. Two lines from the love poem “Love in a Tent in Africa”—“Under wraps the body frets to be free,/to be a me that is you, so be thou me”—essentially encapsulate Oerke’s all-embracing approach to creatures across the board.

I don’t mean to imply, either, that Elephant Cake Walk is not a very serious book. Just for the record, not all the poems are comic, and some that are—for example, “The Great Wing of Night Soaring Across Africa”—are visionary at the same time. One of my favorite poems, “In the Village,” is not comic at all. It reminds me of perhaps the best thing I took out of the Peace Corps—a rootedness in simple, human habits:

In the village, in the village, in the village

life repeats itself, life repeats itself.

There is sunlight, there is darkness. The dark

Repeats itself, the light repeats itself.

Yet life is never dull.

The Elephant Cake Walk is not a flawless book. For example, poems along similar themes (stiltwalkers, witch doctors, African nights, etc.) tend to repeat themselves too much. Still, it seems somehow almost unfair to acknowledge even minor faults in the face of Oerke’s incredible generosity of spirit. It is true, too, that since this is a posthumous volume, the poet may simply not have had the luxury of the time to get to all the editing he wanted done.

Contributor’s Notes by Anitra Thorhaug fill the reader in on the poet’s driving interests (giving micro loans to the poorest of the poor, “healing” the environment after oil spills and earthquakes, restoring tropical habitat along seacoasts, etc.). It is a great credit to the poet that the poems do not leave these commitments behind. Andrew Oerke clearly had a big heart. I only wish I could have known him.

•

Ann Neelon is the author of Easter Vigil, which won both the Anhinga Prize for Poetry and the Returned Peace Corps Volunteer Writers and Readers Award. She teaches at Murray State University and edits New Madrid journal. She recently read at Teatro Paraguas in Santa Fe, NM in the first Southwest Salon sponsored by Irish-American Writers and Artists, Inc.

Bravo for a fine review capturing the spirit and rhythms of Elephant Cakewalk . a

I echo A. Thorhaug’s comment. These reviews on Peace Corps World Wide deserve a book of their own!

for those of us who did know Andy (I was Malawi PCV 68-70), who was both a former Golden Gloves boxer as well as a poet, he was a force of nature in the fullest sense of the word…and one whose heart was as open and sensitive as the energy and enthusiasm he exhibited in the dance of life. Once having met Andy….you never forgot him….