Gypsy Street by William Siegel (Ethiopia 1962-64)

[This is the second in a series of short stories written by William Siegel (Ethiopia 1962-64). Will’s stories are about the folk ‘scene’ in Greenwich Village in the Sixties and Seventies. Will wrote me that the character of his story, Harold Childe, is based on Phil Ochs who took his own life by hanging in 1976, and that the original title for “Gypsy Street” was “The Last Days of Phil Ochs.”

With the passing of Pete Seeger it is perhaps time to pause and recall that time in our lives. To put us in the mood, here’s “Gypsy Street,” Will’s story of life in the Village that he knew so well when he was preforming as folksinger Will Street.]

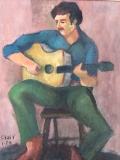

Portrait of Will Street (Will Siegel) by Artist George Cherr, 1976

Gypsy Street

by William Siegel

Near the end of the third winter Floyd and Dwain spent in Greenwich Village, disappointment and frustration drove them like a horse and carriage to a drunken oath one morning after last call at the Kettle. Since they hadn’t made it by then, they swore to jump off the Brooklyn Bridge together and at least get a write-up in the local papers. FOLKSINGERS JUMP IN UNISON FROM BROOKLYN BRIDGE. Of course – Dwain being from Kentucky and Floyd from West Virginia – neither of them knew which bridge might be the Brooklyn Bridge, there being so many bridges over on that side of town. Neither had ever been to Brooklyn. The last familiar sight had been a bum sleeping in a doorway on Houston St. Then, ambling downtown and veering toward the East River, they found themselves lost.

“Only the dead know Brooklyn,” Dwain kept saying. “Only the dead.”

“There’s no bridge down here, man. We got to go over there” Floyd hollered and pointed as they weaved across another street. “We’ll never find Brooklyn.”

They scampered down Greenwich, a couple possums up from the hollow, rooting along a straight line until they came to a hitch, and then turned one way or the other.

“We don’t need Brooklyn,” Dwain said. “We only just need the bridge.”

Among the thin echoes of early morning the two drunken minstrels wandered down a side street headed for the river. “Well, whatever comes first,” Floyd said. “Hey looky over there. There’s a bridge going somewhere near where Brooklyn should be.

“Hey,” Dwain said. “Remember all the WWII movies where the regular Joes kidded the skinny, funny looking guy about being from Brooklyn?”

“Yeah, and he always got shot dead and everyone was mad as hell and running over the hill with a grenade, shouting, ‘This one’s for Brooklyn. This one’s for Brooklyn.'”

“Yeah,” Dwain said. “Brooklyn always got killed and Ohio always went home with a limp,”

“Sometimes, Indiana got shot, too. But Oklahoma and Texas they always made it out alive.”

“Yeah, it’s all the luck, when you’re in the movies – somehow the Midwest don’t pay the same price as Brooklyn.”

“They’re all smart asses in Brooklyn,” that’s why,” Dwain said. “They got this famous bridge and they hide it.”

The two were out of breath, laughing, chattering squirrels retreating to their backwoods upbringing, their lack of sophistication against the background of this perilous, complicated world of New York City. Dwain wore an old brown refugee overcoat buttoned up to his neck. The too long coattails whipped out in back of him when he ran and reminded Floyd of some Marx Brothers movie.

“Yeah, they hid the fucking bridge. Go check the fucking fridge,” Dwain sang.

They laughed, coughing and choking, wandering up the wet pavement. They held their sides running zigzag across empty streets.

“They hid it, the smart asses,” Floyd grumbled through his laughter. “All these foreigners here. They hide it from us real people back home and then joke about selling it, but I don’t think there’s no Brooklyn Bridge.”

“Hey, man, we’re on Duane St.,” Dwain said. “They spelled it wrong. Damn, ain’t that New York? They name a street after you, and then they spell it all wrong.”

They headed across Duane to West Broadway. In a stark and eerie flash of light, they spied the bridge towers looming from the dark night into the brightening sky; the gothic window insets opened on the dimming stars, the string of greenish white pearl lights stretched along its curved cables ─ a ghosted ship docked between island and mainland.

“My God,” Floyd said. “Look at that.”

The two immigrants, struck in awe, stood in their tracks. Then, lurching, as they ran toward it, the bridge disappeared.

“I gotta pee, gotta pee,” Dwain said. He went over to a dark alley filled with cardboard boxes and crates next to a shuttered market and unzipped.

The alley didn’t go through, so they went up one street but they couldn’t see the bridge and up another; laughing and singing and joking in their drunkenness they lost sight of the bridge. They tried to make it to the river, finally, hit or miss, one street at a time until they broke out just at dawn onto the grass of a small park off Centre St. in the shadow of the great bridge. The cathedral towers shot up from the center of the earth and shimmered on the gray water.

“You still wanna jump?” Floyd asked. “Maybe we should just look at it for awhile?”

“No, man,” Dwain said. “We gonna die off it.”

“Dazzling,” Floyd said. He never expected beauty from a bridge. Maybe that could be the difference, he thought. All these big-city hicks took this bridge for granted, used it every day; the chaos burned them out. But for the migrant grown on less grand turf, the splendor and grime nurtured the sterner stuff of ambition.

The two folksingers stood at the park in front of official-looking city buildings and stared. “One hell of a place,” Dwain said. “Easy to get to. More real than a palomino pony, man, we can just walk up and jump right off it.”

“No sweat, Floyd agreed.”

A few cars came and went on the bridge.

They walked across the grass, closer. “Holy shit,” Dwain said. “Holy shit. Look at that.”

“What?” Floyd asked, marveling now at the ghost-lit boulevard leading up to the bridge.

“Ain’t it just like New York to build a jump-proof bridge. I tell you this takes the cake. They put the bridge outta sight. They misspell all the streets so you can’t find nothin’, and they put the walkway in middle of the whole shebang.”

Floyd looked at the bridge and sure enough inside the middle cables an elevated walkway with a stripe down the middle ran the length of the bridge, through the two cathedral towers and on to the other side, which must have been Brooklyn. “Ain’t that a bitch,” Floyd said surveying the bridge on shaky legs, watching a car here and there make the easy turn and lift up onto the bridge.

“Such a hard, long way to go.” Dwain coughed from deep in his lungs, sitting on a bench, weary. “I’ll jump from right here and prob’ly just break my teeth and stove a finger,” he said with faltering laughter.

Floyd could not take his eyes from the silent carnival of cables gleaming through the cold air up and down the length of the bridge. Robust and strong in the shadows of the dawn, the bridge shimmered through its own light. The bridge of Whitman.

“Bigger than life,” Dwain said. “It’s gonna take us through from one stage to the next, like we was passing the torch to another runner.”

“Yeah, now we have to jump.” Floyd said. “We made ourselves a vow to leap from the center of this bridge onto the hard water for all humanity.”

“Yeah,” Dwain agreed. “For the sake of all those who leaped before us and the many who will leap after. We’re gonna be a bridge to the other side.”

Floyd imagined the leap – the stutter-step, the cold air, the dive, the swan song – the last irrevocable breath – the loss of reason connecting one moment to the next ─ no hope of redemption. “Here we are!” he shouted. “Before the fall and after the fall.”

“Come on,” Dwain said. He stood ready to plunge across Centre St..

“Now what?” Floyd asked.

“Let’s just go out to the middle and shimmy down to the car lane. Hell, there’s no traffic. We can go all the way over and take the big leap. Easy I tell you, easy as fallin’ off a log.”

Dwain ran.

Floyd ran, too.

“We’re gonna do it, you and me,” Dwain sang. “Jump on the heaven bound train, yeah, yeah, yeah.”

Floyd joined in. “Bound for Glory on the heaven bound train,” he sang.

The two rag tags skipped up the walkway and ran further next to the trellised steel railing. They ran alongside the cable as it curved down from the first tower and just as it swooped next to them, they stopped, short of breath, wheezing. They looked at each other pleased as punch.

“Over here,” Dwain said. He ran up a few yards. “Looky here, man.” A beam ran from the crosshatched rail over to the trench where the cable slipped down so neatly to the roadway below. “Looky, man,” Dwain explained. “We can balance across this here beam and slide down the cable pipe, run across the roadway and jump.”

“I dunno, man,” Floyd said in a fit of caution. I don’t think we can make it across and then down. Whyn’t we go back to the end of the bridge and then walk out on the car level and then it’s an easy jump.”

“No, no, man” Dwain stroked his mustache. “I ain’t going all the way back there and start over. You chicken or something? Afraid you’re gonna fall off da’ bridge, man?”

They laughed, trying to regain their easy drunken cheek.

Then they were climbing over the rail and along the cables, wheeing and whirring down over to the wound cable wires ever so ginger and then sliding, Dwain first and then Floyd, down the cables, careful not to fall, easing themselves to the car lanes below. Easy, easy, feeling the cold metal on their butts, their hands half frozen and chapped. Their long guitar-player fingernails chipping on the metal as they slid like firemen the last yards and then they were down, running across the lanes of sparse traffic to the other side of the bridge.

Dwain sang out in the wind, “What do you think, man? Headlines at home. ‘Folk singers choose ‘Not to be’ ─ leap from Brooklyn Bridge. Music business mourns the unknown folksingers. Lost souls parade across Brooklyn Bridge in solidarity with leaping folksingers. New York closes down for entire day for lost singers. The Brill building – sad, silent and sorry. Recording companies scouring the Village for the ‘lost demos.’ Here we are man, dig it, in the ruins of your balcony. Oh, mama can this really be the end? We of the flying folksingers, destined to die in the cold gray waters beneath the great bridge of Brooklyn, drowned at the very start of our careers. Fledgling birds soaring far, far into the future. What do you think, old Floyd? They’ll be writing about us for years. Every generation coming up with a song about the two brave singers who flung themselves off the Brooklyn Bridge for the love of…” Dwain paused. “Love of… you know, the love of something. Whaddy ya think?” Dwain asked, finally, thoughtful, winding down and less sure.

“Well, I don’t know,” Floyd replied. A thousand songs of mournful, willful death ran through his mind, everyone died for the love of something – Barbara Allen to Tutti Frutti. “What do we love? We can’t just jump without loving something, man. What are they going to sing about? You got to love something, get rejected and feel bad, man. Then you jump.”

“Looky here, man, we been rejected by the music business itself. Ain’t that enough? Let ’em sing about the Brill Building boys – the Tin Pan Alley duo that couldn’t get signed to a post card. Hey, man they’ll sing about that, man. Oh, Mama, can this really be the end?”

“I’m not so sure, man,” Floyd said into the wind.

“I say, let’s jump and teach ’em a lesson,” Dwain said.

Off in the dawning mist, rising from the river, Floyd perceived ghosted masts of tall ships. He could not tell if they were real, swaying at the mouth of the river, as they must have appeared more than 200 years ago to the ragtag rebel armies of the new republic defending the harbor. What great hearts put out to sea in those tall timbered rigs, he wondered? Not much of a hero, he thought, to throw himself from the bridge haphazard onto the stones of eternity, while the stout sailors who set sail on the great oceans in those frail boats dared the gods to either drown them or reward them with treasure.

Floyd and Dwain stood at the center of the bridge looking over the side. The cold gray waters stirred beneath; the mist looked inviting. They were both getting on the jump vibe when a long black car pulled to a stop and the driver leaned across the front seat and rolled down his window, “Hey, you boys gonna catch your death of cold out here. You got no business joking around, boys. Why don’t you head back across the bridge there to Downtown Hospital? You can almost see it from here.” He pointed with his outstretched chin. “Yeah, get over to Downtown Hospital and tell them Al sent you,” he said in his Brooklyn accent. “I work over there. They’ll give you a cup of hot chocolate and a sandwich. Tell them Al sent you. I’d take you myself, but I got to get to Brooklyn. Go on now boys, get yourself some hot chocolate.” Then, he drove off.

Suddenly, the air changed, a sober wind whipped up and made them shiver. They didn’t feel quite the same, as if Al had stolen their grit.

“Hot chocolate,” Dwain said, trying to keep up the ruse. “Who’s he kidding? You think I’m gonna trade paradise for a cup of hot chocolate?”

“Maybe he’s right.” Floyd said. “Maybe he knows something we don’t know.” “Sure he does man, but then he don’t know what we know. I’m gonna jump.”

“Don’t do it.”

“Naw, man. I’m all set to jump. I can’t turn back now. It wouldn’t be right.”

“Sure it would, man. We could write a song about the mysterious stranger that saved our lives.”

“Sure,” Dwain said. “Man, I really think we should make the leap. Paradise, man. From here to eternity, man.”

“No,” Floyd said. “I’m going for the hot chocolate. Maybe a sandwich.”

“Man, you get bought cheap.” Dwain put his boot on the lower rail and boosted himself up. Floyd reached over and pulled Dwain off by the tail of his brown coat.

Dwain turned with a sharp angry look, a look Floyd had not seen before.

“You got no call to do that,” Dwain said. “This ain’t no dress rehearsal rag, man. I’m going.” He started his climb over the railing once again.

Floyd, for the first time that long night, felt terror. He took a startled step closer to Dwain, and with all his might slammed the palm of his hand on the flat of Dwain’s shoulder – a blow which brought his friend to one knee. Floyd saw the tears glisten in Dwain’s blue eyes as he knelt on the cement, leaning against the iron paling for a moment or two. The dawning light spread above ghosted Brooklyn. The wind whipped at their coats and burned their hands raw and red. The tensions that had sometimes come between the two during their daily quests came to the fore. For a moment, Floyd thought Dwain might wrestle him over the side. He could hear a roar forming deep inside Dwain’s belly.

“I knew you were going to do that,” Dwain choked, finally, wheezing and out of breath.

Floyd took Dwain’s hand to pull him up. “Yeah, I know. Let’s get some hot chocolate, man.”

“Yeah, man, hot chocolate.”

Then they got to laughing and raced back toward Manhattan on the side of the car lane. They never found the hospital, and continued on the slow folksy train to oblivion, and never once talked or even joked about that night.

For several evenings toward the end of March, Harold Childe, the once famous folksinger, with hit songs such as There You Go and Don’t Draft Me sat alone at a table in the Kettle, a narrow sawdust saloon on MacDougal St. People in the know called Childe the Gold Coast King after he put on a concert a few years back at a slick San Francisco venue, and no one came. He never lived it down. Childe sat at a small table against the wall opposite the long wooden bar lost in the echoes of his rebel youth, lock-jawed and wrung out, staring at ghosts, the faintest of smiles on his lips.

Floyd, from his perch at the bar studied Childe with a combination of awe and terror. Every time Childe moved Floyd shifted in concert.

“Go on over and talk to him,” Dwain said from the next stool. He kicked the bar for emphasis. “He don’t give a hoot.” Dwain cocked his head toward Childe.

Floyd bit his lip.

Eric looked up from the Daily News. “Every owl gives a hoot.” He put his elbows on the bar and returned to the paper.

A picture of Old Ironsides splashed across the front page. Framed by the Brooklyn Bridge the ship swayed on the water with sails full and narrow streamers flying from the twin topmasts, cannons ready. A contingent of sailors dressed in berets with dangling ribbons, wide trousers and striped shirts stood on the foredeck saluting. The ship had sailed into New York harbor the day before to publicize the gaggle of tall ships that would assemble in July to celebrate the 200th Anniversary of the Republic.

“All you hear about are tall ships,” Eric said with impatience. “Space ships – now, that’s something to put on the front page, man. Some wind-powered rigger from 1776 is no news to me.” He shook the paper open to reports of Florida sunshine and spring training. Flecks of late winter snow melted on the window.

Several folk singers of various sorts in various stages of disgruntlement occupied the creaky bar stools, waiting to walk around the corner for Eric’s late set at Folk City. A few other patrons talked at tables along the wall. Childe, bloated and overweight with red splotches on his face, sat facing the door with his shoulder against the wall at a table between the jukebox and the pong machine. He wore a dirty white shirt, a shabby leather jacket and a peaked cap with his hair sticking out around his ears. Pauley, the bartender, had parked a draft in front of him an hour before, but Childe never touched the mug. His head turned from side to side, focusing off into the distance for a moment and then shifted again while he shut his eyes hard and scowled. The three at the bar watched Childe with deep attention.

“Bad haircut,” Dwain said. “Still lost in the glory days.”

Eric looked up from his paper. “Somebody tell the old boy it’s over. I burned my draft card and my bell bottoms, too.”

“He’s a walking antique from desolation row,” Dwain smirked.

“He suffers from the disease of the sentimentally deranged,” Eric said, shifting his gaze to Floyd. “Pretty Boy here better keep away or he’ll catch it, too.”

“Naw,” Dwain said. “Floyd’s gonna get him to talk. We got a bet.”

“You guys don’t know. You’ll never know,” Floyd said over his shoulder, keeping his eyes glued to Childe.

“A bird on a wire,” Dwain said. “Look at him, man. He’s a loony.”

“Oh yeah,” Floyd said, picking up his beer. “You’ll see. He’s coming to his senses right here where he started.”

Floyd’s first impulse had been to avoid Childe who caused Floyd to suffer the depths of his own predicament. He felt ashamed for wanting to pass Childe by, but also obliged to find a way to talk the older singer out of this soul sickness. If I could call up a little cheek on this fellow, I would feel a lot safer, Floyd thought. He didn’t know where to begin.

Dwain snickered when Floyd stood up and kicked the sawdust off his boots. “You got yourself a beer if you get him to talk,” Dwain said.

Floyd walked toward the jukebox. Childe appeared lost as a misplaced key. His moon face shone wax white behind the splotches and a three-day growth of beard. His eyes did not to fit into their sockets as they shifted, staring out the window or above the horizon of the bar through the array of dusty bottles. Floyd tried to see him as he used to be, when the young Childe, thrumming and impatient, burned to put the world right with a blasting fusillade of words. Floyd stood before the jukebox for several minutes, his eyes running over the tunes of the many musicians and songwriters who passed through the Kettle and on to better things. He pretended to pick out a tune, waiting for Childe to look at him. Dwain coughed and cackled.

“Hey, Harold,” Floyd called out after a time. “What’s going on?”

Childe paid no attention.

Floyd found the courage to mosey over and sit in the chair facing Childe.

“How’s it going, Harold?” he asked, placing his elbows carefully on the table. A big pounding came up in his chest. He prayed for words, any words to pass his dry mouth. “Almost ten years later and we’re still living in the dust of the 60’s, Harold,” Floyd began in a halting voice. “Here we are on the bridge to the country’s 200th. Tall ships sailing into the harbor, and we still haven’t got it right, Harold.”

Silence.

“Come on Harold,” Floyd picked up the pace. “Give us some of your courage, man. The music can do what it did before. You’re the only one we have right here with us.”

Childe stared off in the distance. For a moment Floyd thought he could hear the winds of the older singer’s words whirring around his brain. Dead silence.

After a time, Floyd tried again. “Must be a blast to be back in the Village, Harold? You musta been in California or Paris or someplace like that for a long time, but you started out here, downstairs at the Gaslight, right? We’re a new crop these days and thought maybe you’d have some advice for us or something.”

Dwain sang in the background. “Here we are, Harold Baby, in the ruins of your balcony.”

Childe turned his head. Floyd held his breath, thinking the singer might say something, but he only wrinkled his nose. “Dogs are loose.” Childe said finally, looking out the window.

Dwain strummed his hand across his chest, signaling Floyd to keep at it. Though Floyd detected despair and torment crouching behind Childe’s eyes, other secrets remained, secrets the younger singer could not fathom – perhaps a clock about to strike or a spring to unwind. Floyd sipped his beer and watched Childe for a while longer. Sometimes Childe moved his head, but he never said another word, only the darting, wary look of a bird. After a time, Floyd stood up and Childe stood with him. They appeared to be getting ready to leave together, but Childe shambled out the door and into the street without a glance back.

Floyd went over to Dwain and Eric. “Hey, Dwain,” he said. You owe me a Heinekens.”

“I said he’s got to talk to you,” Dwain wailed in his Kentucky drawl. “Any body can talk to ‘im.”

“Hey, man, Floyd answered. You heard him.”

“That wasn’t talking, man. That was mumbling.”

Other than Doc Watson, Floyd never heard a cleaner guitar-picker than Dwain, who claimed his poor daddy could only afford a handful of flat-picks for toys.

Eric sang broadsides from the Scottish moors and blues, too, in a raspy angular voice over a pretty good bottleneck guitar.

“You owe me a Heinekens,” Floyd told Dwain.

“I don’t buy any of that foreign crap,” Dwain said. “You don’t know what you’re getting from over there.”

“Sure,” Eric said, holding an amber mug to his eye. “Down in Kentucky they do the brew with pure possum piss.”

Childe had disappeared by the time Floyd got himself to the door. He had a guilty thought to look after the old boy and the guilt stretched into a glimpse of his own profile slinking back to the river town where he’d spawned. The snow turned to rain. The sidewalk, wet and shining, reflected streetlights and neon signs lighting up MacDougal Street like a carnival midway. The rain hummed on the pavement. People pulled their coats close as they trundled up and down the street. Floyd turned and looked at the scene inside the Kettle. A few people hunched at the bar and tables – all waiting for a break; a break in the weather, a break in the night, a turn of fortune, some streetcar that would sweep them up to the Brill building long enough to sign a contract, a sweet deal riding on a long draught of beer that loosened the throat and satisfied the thirst. Feeling lost to himself, Floyd returned to the comfort of the bar longing to be stamped into a new coin and slipped into the jukebox.

Eric stood and picked up his guitar case. “Tall ships. Shit, man, they ain’t that tall. It’s all advertising so they can sell T-shirts and balloons and get themselves re-elected.”

Several times in the next week Floyd watched Childe wandering along MacDougal Street – one more muddled soul scuffling through the Village. He reminded Floyd of questions and doubts about his own life. “Man,” Floyd talked to himself out loud, breathing into the collar of his pea coat, “If you got any doubts you shouldn’t be here. You got to stamp out the doubts or get out of town, my man,” he argued. But here he’d come to be. He shifted his guitar case from one hand to the other. He couldn’t quite admit that Harold Childe appeared the image of Floyd’s worst fears for himself.

Some nights Childe turned up in the music room at Folk City floating on the vapors of an angry stupor. He paid no attention to Floyd or any of the various acts – folksy singles, bands, duos, bebop or blues – that crossed in front him. Instead, he leaned forward in the smoky air, straining to hear music from beyond the room. Sometimes Childe sported a carpenter’s hammer that he pulled from under his coat and held in his hand as if ready to nail a door or coffin shut.

When the hammer came out, Floyd had to go outside and smoke a cigarette, pacing back and forth. “If I had a hammer,” Floyd sang to himself. “There but for fortune…” he sang. Floyd tried to get the words out of his brain. The next moment Floyd bit his lip in remorse and tried to talk to Childe, but barely got more than a quick absent look. Besides, Floyd had his own problems. He’d been drinking too much, staying out every night until the bars closed. He’d sleep until eleven; blow a joint, hunker in his room all day playing guitar and working on his threadbare songs. Being stoned all the time proved the only way he could face the daylight. Some nights he played a set or two at the Fat Black Pussycat or the Cafe Wha and passed the hat. Around ten a thirst came over him; he’d head over to the Kettle for a few beers before hitting Folk City where Eric or someone might invite him to sing a chance song or two.

Folk City, in the decade after the glory days of the Village folk scene, became the spiritual beacon for the singers and songwriters who came afterwards – the younger brothers and sisters of the group of greats who created the music and the movement of the 60’s. They came to profess their own talent and swing by the threads of that glorious past into something of a movement of their own. Folk City, around the corner from the Gaslight, had already become a tourist attraction as the place where it all started. Under a small red awning, black-framed pictures of Dave Van Ronk, the young Dylan and Joan Baez, along with Carolyn Hester, Tom Paxton, Phil Ochs, Judy Collins, Childe and a dozen or so others looked hopefully out of the dark windows onto the bleak street. Their names were listed with the dates of their first appearance at the club. The dates, hand printed in black lettering – Dec. 4, 1962; Feb 16, 1963 – were more real than the faded publicity shots. The homemade lettering spiked the young singers and songwriters who were crazy to recreate those days; as if passing through the doors of this club could spring them onto the stage of casual, unassuming, accidental fame.

Floyd dreamed of being an entertainer, though he never suffered the authentic call of this restless band of folksingers. The dream in his mind’s eye remained vague – the details too unnerving for the shy West Virginia boy to fill in. He was caught between a belief in himself and an unspeakable loyalty to the fear that he would never be good enough; that he was born shy a few straws on every account, that he was born with less than others were given. Sometime during his childhood he assumed this loyalty to calm an hysterical mother – to prove her fears right and his own star wrong. Nowadays, from the stage, he could not embrace the joy of touching an audience. These Village musicians possessed a gypsy spirit that frightened Floyd – screaming and chording, slamming their boots on the slats of the stage, rasping out their dreams to the paying customers. Fly-by-nighters, they hovered from one flame to the next. He did not trust their reckless ways, with their nothing to lose attitudes, their brash indifference to the brick wall of fate. Yet, he loved to be around their bold irreverence and feel a part of the raucous music. He remained frightened and fascinated by their willingness to lay their bodies down for the long shot over the bow. Though he was bound to leave these gypsies, some figment of pride prevented him from admitting he did not possess the swagger and talent to be one of them. Instead he struggled with his mournful, talky songs while he thrashed about unable to give up the hunt and find his home. He could not escape his boyhood cast.

Eric advised Floyd to forget the message and push the music, but Floyd could not find the cloudless sky to sing about. “Get a band together and make a demo for Christ’s sake.” Eric raised his right eyebrow and let Floyd have it one late night at the Kettle – bar stool to bar stool. “These modern music moguls in jeans and fat sideburns are not going to give a second listen to songs with a solo guitar and your reedy voice. Get up-to-date, man. The ’60s is over. Get yourself a band. I’ll score you some comp time on Eighth Street. Fuck, man,” he said. “We’re not back in the day any more. You got to make up your mind and shoot your arrow, man. Don’t be afraid to hit your mark. Everyone’s afraid. I’ll help you get your demo together. And then, man, hell and high water. The tall ships man. The fucking tall ships will take you away. All you need is a demo man. Sail away ladies, sail away…”

Among the singers and songwriters around the Village, the word demo buzzed. That’s how to get the deal nowadays. Make a demo that sounded as good as a record and they might listen to you.

“Yeah, man,” Floyd confided. “I got a band. Me and Dwain we got a band called The Jumpers or as we’re known on the coast, The Mediocres.” He laughed.

Childe turned up again when Floyd and Eric and Dwain were camped at a table in the front room at Folk City. Childe walked in wearing heavy work boots and a Stetson hat. He looked a little more together than usual, like someone had dressed him.

“Go over and ask Harold to sing on your demo,” Eric said to Floyd. “He might just do it.”

“Sure,” Floyd said. “He doesn’t recognize anyone, doesn’t talk to anyone, so he’s going to sing on my demo. Every time I try, he talks to the wall.”

“He give you some words the other night. Worth a try,” Dwain said, scratching his sparse blond beard.

Childe looked to be perched on the verge of madness. His eyes were wide, his face, red and masked with disbelief. He never looked one way or the other. The bulge of the hammer stuck out from the pocket of his thick sheepskin coat.

“Hey Harold,” Floyd said, walking toward him, still a few feet away.

Childe stared in his direction trying to figure out did he know Floyd.

“Bobby?” he said. Then, looked away.

“Good to see you around,” Floyd said, walking up to him.

“Jack?” Childe asked. He tugged on his hat and looked up at Floyd from under the brim. His eyes might have been living in another century.

“What about coming down to the studio,” Floyd said. “I could use some help on my demo.”

“What?” Childe asked.

“I could use some help on my demo,” Floyd repeated.

“I don’t sing anymore, Bub,” he said with some clarity. The bulk of his body swayed. His eyes steamed. Why don’t you know that, they asked? Childe looked past the younger folk singer.

“Thursday evening,” Floyd went on. “I have some time booked on Eighth St. If you could make it, I’d be obliged.”

“Obliged,” Childe said, picking up the word. “You’re obliged all right. We’re all obliged, Bub. What comes after?”

“Do you think you could make it Thursday about eight?” Floyd asked. “Easy to remember. Eight on Eighth St.”

“Who isn’t obliged, Bub?” Childe repeated, getting excited. “We’re all obliged. What comes after, that’s what matters,” he said.

“I don’t quite get you,” Floyd said, his voice trailing.

Childe stared off into the distance and paid no more attention, leaving Floyd feeling foolish and naked with people at the bar staring.

Floyd returned to the table where Dwain and Eric sat close to the back room. “What’d he say?” Dwain showed a toothy grin.

“We’re all obliged,” Floyd told Dwain.

“Is he going to do it?”

“He didn’t say. I told him where and when. I don’t know if he heard me or not. He kept calling me Bub”

“Yeah, he’s lost in the glory days, man.”

“I don’t know,” Floyd said. “I think he calls everybody Bobby or Bub. He called me Jack, too. Why don’t you go over and talk to him.”

“If I had a hammer …” Dwain sang.

“He’s harmless,” Floyd said. “He’s distracted is all. Maybe he’ll show up.”

“Yeah,” Dwain said. “That would be something. Everyone would be impressed if you got Childe to sing your songs.”

“I told him I’d be obliged,” Floyd said.

“Obliged? He could make you into something. You’d owe him your life, Bobby.”

“Sure,” Floyd said. “I owe you my life, too. Anyway, the Brill’s have to like the song, they don’t care if Harold Childe sings on your demo – though I guess it couldn’t hurt.”

On Thursday morning Floyd woke a few minutes after eleven to the tune of ‘Don’t Draft Me” ringing through his head. He’d been playing the guitar so much over the last couple of weeks that he didn’t want to pick it up or even look at it, but made himself spend the afternoon going over the songs. They’d scored the studio on spec. Eric had written out some charts. A couple of people from around the village agreed to back him on guitar and drums. If he could get Childe in there, just to sing on a chorus that would be a plus. People would listen.

About six o’clock Floyd packed up his guitar and went down to a joint on Sixth Avenue under the Folklore center for good luck. He carefully leaned his guitar case next to his place at the marble counter and ordered meatloaf, mashed potatoes, string beans and a coke. He poured ketchup on the meat and ate slow, feeling the food full and warm in his gullet. Then, he walked around MacDougal Street, bare and creepy at that twilight hour between offices closing and the clubs opening. Walking up and down the street with his guitar swinging in his right hand, he glimpsed his reflection in store windows imitating the cover of a Dylan album; thinking he’d give half his future to go back and catch a piece of that time. He walked up to Bleeker St. and then again to Third St. on the other side, marking out his territory. He burned in the chill air to be the young Childe or Dylan.

At the corner of Bleeker and MacDougal, Floyd spotted Childe sitting in the side doorway of the Café Figuero, the new coat already shabby, the battered Stetson sliding off his head. A foggy twilight spread through the streets, smelling wet on the pavement.

“Hey, Harold,” Floyd yelled from across the street. Childe did not move. He had that abstract, disconnected look on his face. People walked by without noticing.

“Hey, Harold,” Floyd said, crossing over. “Can I buy you a coffee or something?”

Childe looked at Floyd and hauled up his heavy body, first on one knee, then pushing up from the leg, then the other leg, just as if they’d made this plan days ago.

“Where you been, Jack?” Childe asked.

“Want to go in here?”

With his hands in his pockets, he shuffled inside behind Floyd. They sat in the back room by the window. Harold never looked at Floyd, but slouched in his chair, the Stetson askew. He appeared weary and looked around right and left and over his shoulder.

Floyd ordered two cappuccinos. When the steaming cups arrived, Harold cocked his head and looked puzzled.

“What you got going on?” Floyd asked. He should have known by then that Childe brokered no hope, but he could not throw off the thought of Childe on his demo, or that he was having coffee with Harold Childe.

“So, you gonna come help me out?” Floyd asked. “What do you think, Harold, man? Want to sing one of my songs in the studio with me?”

Floyd waited several minutes. He followed Childe’ stare through the window to get in tune with him. He could make out no movement on the third story of the building across the street where Childe squinted – just a row of lighted windows muted with red checkered curtains. Neighborhood people, Floyd thought, maybe a few artists, lived up there in rent-controlled apartments with ice boxes and bathtubs in the kitchen. Old, dead gaslights on the wall, faded wallpaper, bathrooms in the halls. He wondered if he could be destined to spend his own life in one of these cramped apartments. What could Childe find here – some piece of his past that would make him whole again? Staring down walls. Trying to find meaning in his life again? Maybe he’s going mad, but madness in the mid 1970’s came off mundane and ordinary compared to all the people who ended broken and batty in the ’60’s.

No, Floyd thought, I can figure this guy out. I can help him see his way clear. Harold continued to wage his own war – North Vietnamese Army on the left, the U.S and the South on the right, generals in the rear, ships and air force in motion – smoking jungles and young boys in pajamas and body bags. Weeping mothers, searing flames painted across old Harold’s brain, living in his own Guernica. Death, larger than life, more precious even, a cause he could die for. Childe, struggling in the solar wind and Floyd feeling shame and dread trying to reel him in; wounded in the reflected breath of excitement from the wars, the protests, the drugs, and the music – the ruins of your balcony. For Christ’s sake, get me out of here, Floyd thought.

No, Floyd wanted to vault into the past, ride the winds of that time when Childe and the whole rocking movement had a purpose – he could not shake the ties that bound him to his loyal past. He could feel the power twisted around the old singer’s brain. Here he’d traveled far enough to sit across the table from him. He’d traveled from being a kid sitting on his bed struggling with chords and picks, and listening to Childe and Dylan, Ochs and the Weavers, Peter, Paul and Grits. Here he’d arrived and the oracle flame had burned out. The hopelessness made Floyd want to cry. Only he couldn’t. He didn’t want to care anymore. He really didn’t. He only wanted to be gone somewhere. He wanted to be far away, but Childe’s face, barely familiar, brought him back.

“Hey, Harold,” he said in a charged, desperate tone. “Why don’t you come on down to the studio for awhile?” Then he softened, “Hang out. Do whatever you want. Sing on my demo or maybe you got a new tune you could lay down.”

Childe looked away from the window and directly at Floyd for a short moment. The gauze unrolled from his eyes and then rolled right back up.

“Hey Harold, it’ll be a blast, dancing girls and all,” Floyd laughed. “No worries. Just good times.” Childe never looked at Floyd. His mind or his eye – who knows if they were connected – remained on ghosts across the street.

When Floyd stood up to leave, Childe followed down MacDougal a couple stumbling steps behind. The younger man tried not to look back, but every few minutes he had to make sure Childe kept up. He felt a kind of sinking hope on that walk on his way to record with a band. The moment should be a high for him, only he couldn’t feel it real clear. He had a thought about a step in the right direction – how if he could get Childe to sing, – all thoughts with no feel. Floyd knew he was missing something but he didn’t know what – he thought it might be Childe.

Quarter to eight, at the glass door next to the High Stepper Shoe Store, he rang the bell. “Floyd Webber and friend,” he said when Liz’s voice came through the speaker. The door buzzed open. He held Harold by the arm, guiding him down the dim curving staircase. Harold reached up and patted the carpeted walls as if he couldn’t make out the wall from the floor. The old boy tripped on the last step. Floyd saw a grain of consciousness in Childe’ eyes as he sat on the steps and rubbed his knee. Floyd didn’t expect anything so human and natural. Childe looked up at Floyd, “More than a shot of whiskey.”

Liz, wearing boots, tight jeans and glasses with a no-nonsense look on her pretty face, came out of the office. “Eric and the others are setting up,” she said. “Who’s this?” She looked down at Childe, still sitting on the step. “Oh,” she said. “And what’s he going to do?”

“He’s going to fall up the steps, I guess,” Floyd said.

Around the corner from the office dials and gauges glowed from the padded console in the dark paneled control room. In the brightly lit studio adjacent, Billy Childers sat at a drum kit smoking a cigarette. Two high stools faced the control room. An electric bass player, who Floyd did not know, sat with his instrument draped across his front, pulling at the strings in rhythmic snaps. The scene, resembling the back of a rock album out of the sixties, took Floyd’s breath. They had come together to play with him.

Eric leaned against the console in the control room talking to the engineer and Dwain sipped at a coke, keeping an eye on Liz.

“Hey, Harold,” Floyd said. “Why don’t you join us?”

Childe didn’t seem to comprehend, so Floyd took his arm and led him to a couch next to the coke machine with a view of the control room and the studio.

“Is this some kind of movie?” Harold asked, addressing Floyd for the first time. “Are we going see ‘Wake up in Peace’?” he asked like a kid.

“Yeah,” Floyd said. “It’s all a movie. We’re going to wake up in peace and you can play the guitar and sing. It’s that kind of movie.”

Harold gave Floyd a dim smile. With a nod of his head a look of recognition flashed across Harold’s face.

Eric walked out of the studio. “You reeled him in, man.”

“What’re we going to do?” Floyd asked, trying to conceal his worry. “I mean what songs and who’s going to play what?” All of a sudden Floyd couldn’t think straight. He’d planned it all out with Eric over a week ago at the Kettle.

“Whataya mean, man? We got a plan. Where you been?” Eric stared at Floyd’s hands, causing Floyd to follow Eric’s eyes which led to finding himself wringing his hands like some guilty character in a movie.

“I need me a coke,” Floyd said. “I don’t feel well.”

“You don’t feel good ’cause you’re on the spot,” Dwain said, walking over. “Get off the spot. Looky here, Pretty Boy drug in the hammer man,”

Eric nodded.

“He’s afraid,” Dwain said. “Pretty Boy’s never been here before.”

“Sure I have,” Floyd said. “It’s not now; it’s my past got me at this minute.”

“You got no past in here bubba,” Eric said.

“Hiya,” someone said from the carpeted steps.

Floyd looked around; Casey Scroggins walked in, a fellow who played lead guitar on recording sessions all over the city. Floyd had met him once or twice. A friend of Eric’s, he’d agreed to sit in as a favor. He was at least six feet four and wore a black planter’s hat and a fancy buckskin coat with fringe and red embroidery. He swung his guitar case by the handle – a workman carrying his toolbox.

“Hey, Eric,” he said.

Eric handed him a half-smoked joint. “Hey, man,” Eric said. “This is Floyd Webber, the guy I told you about who writes songs you can’t dance to. He needs a lot of backing up.”

Scroggins didn’t seem to remember Floyd. He shook hands. “Good to meet you,” he said with a slight Southern drawl.

“Welcome to “Night of the Living Dead,” Eric said. He motioned his head toward Childe on the couch.

“Hey, Harold,” Scroggins said without missing a beat.

Harold looked at him with some recognition, but didn’t say anything; his eyes narrowed.

“I got some charts for you,” Eric said to Scroggins who took out his guitar and walked into the studio. Before Scroggins took his coat off, he plugged into the amp, tuning his custom Gibson that shone, Floyd imagined, the color of a Stradivarius. Everyone moved into the studio.

Eric became all business. He set up a music stand and microphone in a vocal booth at the back. He bopped to and fro between the studio and control room setting levels with Ted, the engineer, who resembled a piece each of Crosby, Stills and Nash, hovering over the levers and dials in the control room.

They planned to lay down the basic tracks for four songs. Floyd would play some guitar, too, and then later, if they had time, lay down the voice track.

“Stop paying attention to Liz and pay some to us,” Eric snapped at Dwain.

Dwain would play rhythm and do some fancy flat-picking on breaks. He and Casey had played together before. Floyd, the only one who never played with a band, appeared as lost as Childe.

“You’re a solo act,” Eric told Floyd. “Flying so low we can’t see you; that’s why you need a band, man. We’re gonna fix that.”

“Oh, yeah,” Floyd said back. “Here we are now, The Jumpers.” With all the paraphernalia of the music world crowding in, Floyd could barely breathe. “It’s the words, that matter,” he said in defense.

“Look who wrote the words for Bach,” Eric said, spreading the chart for the first song in front of Casey.

“It’s one, four, five,” Eric said with a touch of disgust. “Folk music. Give us a little intro run on this progression here, kind of a march, you know…something like…”

At that moment, Harold Childe walked through the studio door. His face had completely changed. He held a guitar in one hand and a coke in the other. He had a smile on his face, which brightened his complexion to a rosy glow. “This must be the place,” Childe said.

He looked 15 years younger.

“Wanna play, Harold?” Scroggins asked. “Study in on this chart here with me.”

After that moment of entry, Childe’ face turned ashen again. His arm holding the guitar drooped and he looked around with the air of a devotee set down in a foreign church. He looked at the coke bottle like it had dropped from the sky before he set it on a table; He appeared lost, on the verge of anger.

“Hey, Harold. Remember this,” Scroggins said. He picked out the first few notes of ‘There You Go,’ and grinned at Harold.

Childe showed no recognition of the tune. In fact, he turned the other way positing an impish manner and peered into the control room at the blinking lights. His bulk made him look all the more unreal, as he peered at his reflection in the window glass, fascinated, trying to make up his mind about something. What’s real, the reflections or the lights beyond?

Standing next to Childe, Floyd saw his reflected self, too, with the guitar strap slung around his neck, the guitar, like a shield across his chest. He didn’t recognize his face, but it didn’t make any difference. A crazed sort of glow reflected in the smoked glass. He should look happier, for all the years and knocking around to be right there, but he felt no joy. The knot in his stomach exerted itself – now he knew that’s what he was loyal to. His face stared back in hard straight lines as if he’d been drawn for a comic book – undernourished from another world, a stranger to himself. He looked at Childe’ reflection next to his. Painted in the eerie light, Childe looked whole and real while Floyd saw himself shabby, and colorless. He thought for a moment that he might soon become Childe’s crazy twin. After all, Childe belonged in a recording studio, while Floyd, a true fraud had forced his way out of defiance, out of loyalty to a joke. He had not really been called. He’d been hunting for fame and fortune and not himself. He turned out what he’d feared most, a complete fake. Revealed in that instant, standing next to Childe, Floyd lost all desire. He did not have to speak for a thousand years. Small leaves of flame licked the light off his brain. Buoyant and free he never had to sing another song or try to be what he never could be. For a moment he imagined Childe might be driving these thoughts inside of him. Perhaps Childe’ crazy thoughts wound themselves inside Floyd’s head and steamed into his brain. Floyd felt hot and suffocated as if he’d been swaddled inside a blanket. He wanted to run out of there and be free. He wanted something more. He wanted something deeper.

“All right,” Eric said stepping from the control room into the studio. “We’re going to start with ‘Jefferson County.'”

“Start us off, Billy. Give us a movement beat on the snare, a steady motion like a train picking up speed,” Eric told the drummer who sat smoking the whole time. Then Casey’s gonna come in with a little fife riff.” “A one, two, three. Dwain, pick out the tune since you know it. And if you can find time to tune your guitar, Floyd, you can join in or you can go out in the hall and finish your coke.”

Hearing his name called from another shore, Floyd started. “Sure, Eric.”

“We don’t really need your guitar. Why don’t you just go back there in the booth and do the vocal. Put the earphones on and sing. The band can hear you, but I won’t record you until I get the basic tracks.” Floyd could see Eric felt at home, in fact everyone looked happy except Childe and Floyd. There but for fortune took on a new meaning for him.

“I’d like to play on my own demo,” Floyd said, though his thoughts ran in the opposite direction: You boys go ahead and do it and I’ll head out for awhile, have a cup of coffee, look out the window at all the people passing, think my own thoughts and no one’s the wiser. Then, when it’s over, I’ll come back and have a listen.’

He shook off the craziness he’d contracted from Childe.

Going into the booth at the back of the studio Floyd felt a rush – began to relish his first recording session, first band, first demo, and first chance. A small voice, the color of beer, sang in his head, “You’re the entertainer. You’re the entertainer.” It sounded a note of mock disbelief, while behind this voice Floyd’s eternal question hovered. Why are you doing this? You’re a fraud, you’re a phony. Be loyal to the one who loves you and run out of this place. This is no way for you to make your way in the world. “Wait and see,” Floyd answered as he watched himself float off the Brooklyn Bridge. He pulled the earphones over his head. He could see the whole band through the window in front, as clear as playing pinball at Arty’s. Let go the lever and the ball would bounce all up and down the board, careening through the alleys, squawking, lighting lights and ringing bells. A little nudge here and there. To his surprise he loved the game after all.

Childe picked up the guitar and held it against his chest. He looked ready to play. He’d taken his coat off and his shirttail was out revealing pockets of flesh between the stretched out buttonholes, and overflowing his pants. He stepped right up to the microphone stand and ignoring the others began banging on his guitar. “Bla ba bla, ba bla, ba bla,” he sang. The musicians looked at each other with amusement. Childe went on, “bla, bla bla-ing” in this way for a time as if he were singing a song. Scroggins jumped right in. At various times, Billy Childers and Casey played behind him on drums and guitar. Floyd hummed along in the booth. Dwain started strumming his guitar and Childe’ voice became stronger. He threw in some, “Doee, dodo bop de wops,” along with the “bla, ba blas.”

Soon, everyone found themselves playing together, going along. Childers put more rhythm in and Eric came out of the control room and picked up a guitar. Harold took the lead, singing his nonsense syllables while the tune had the feel of a hymn or folk song turned into a country tune. From the back, Floyd watched the band playing, lurching along, an old wagon on a country road. Not bad, he thought. Childe, even in the depths of his own despair carried a tune in his head, putting it out there, a musician without words, “bla, bal, bla, dodee dodo de bop, getting the inside of his mind out in the open. Childe danced for a few moments on the power of his being; inspired by his mangled presence, the band played on. Childe smiled, and laughed as he sang his nonsense syllables. Here stood the great Harold Childe alive with song. The band followed his tune, winding through the studio, bouncing off the walls. “Bla, bla, bla and do dee do,” they were all riding the tune. A real band, as real as the ones who rode with Jessie James? They were a band of gold wrapped around the fingers of countless kings, a band of tree rings counting out the years, a band of hooded bandits robbing the rich – with Harold leading the way. “Bla, ba bla, doode do do.” They were transported, taken to another dimension where Harold had been dwelling all this time; he unraveled a secret to them, picking the notes from the mystic plane, pronouncing words that everyone could understand.

“Come with me,” He sang. “Come with me,” his syllables led the way. He took off, taking the band with him, led them up and up to a place where all the notes blended. Riding on a plane and then at the crest the sound stopped, and trailed into a rattle. He let the guitar slip from his grasp and drop.

He looked around, puzzled, scratching his head and looked out the door, deciphering his next move while trying to figure out how a door worked. Then, comprehending, he went through the looking glass. The band remained still in the moment of echoing silence eyes following after Childe as he tramped through the lobby and up the carpeted staircase. He walked as if he were following some kind of radio direction inside his head. Floyd and the rest followed him out of the studio. He looked back once, from half way up the steps to smile a strange, open smile of good will, a smile that Floyd had never witnessed during the last weeks Childe had been around. His face shone, unencumbered by meaning or innuendo ─ an owl smile – no ambition, no recrimination, no case for the defense, no thoughts of disbelief, no mourning for what might have been, only the pure smile. Then, Childe shuffled up the stairs and the door slammed with an echo.

Floyd felt a strong urge to follow. He felt guilty. He remembered that first night he’d tried to talk to Childe and let him disappear out the door of the Kettle.

“There he goes,” Dwain said without his usual cynicism.

“OK, OK,” Eric said. “Enough weirdness here among you that thinks you knows what you’re doing. Let’s get back in there and lay some tracks down.”

“Sure, sure,” Casey said.

He and Billy Childers and Dwain wandered into the studio. Floyd walked to the stairs, balanced his boot on the first step prepared to follow Childe. He wanted to follow Childe. In another heartbeat, yanked by an invisible string, he allowed himself to be drawn back into the basement studio among the blinking lights and popping musical notes. Some tether stretched to breaking at the back of his head felt set to pop. The loyalty to some unknown and forgotten cause had snapped. The sticky fear drained from his veins. The heart-stopping rush of ambition wrapped itself around his body from toes to forehead. He walked into the booth at the back of the studio and put on the headphones.

A few days later Eric pulled everyone together for a quick two hours in the studio, persuading another friend, Donnie, to come in on harmonica, and a fellow named Cat to fill in for Scroggins. Dwain didn’t show. Billy the drummer turned up heavy-eyed with his shirttails hanging. “Hard day’s night,” he shrugged, as he sat stiff at the drums. Liz peeked out of the office and pointed to her watch. They waited a while on Dwain, and then Ted, the engineer told Eric they better get going so Floyd went into the booth at back of the studio and laid down the vocal along with the rhythm guitar to Jefferson County. His voice never felt more dry and stretched. Still no Dwain, so they put down the harmonica, bass and drums, which were a little rocky. Eric said the band would even everything out, but Floyd’s scratchy voice, and country guitar didn’t even anything out. The whole time he sang, Floyd wanted to up and run out of the studio. What happened to that ambition from only days ago?

After about an hour, when the lead guitar track was down, Dwain showed up drinking a coke. He stood outside the control room where they all were listening to the last take, and motioned for Floyd to come out. “Hey man,” Floyd said, suddenly all business. “You come in and listen so we can at least lockup one song before we leave.” Dwain shook his head and waved the coke for Floyd to come out.

When Floyd came through the door, Dwain said real slow in his most earnest Kentucky drawl, “Childe is dead. Hanged his self.”

Floyd didn’t comprehend the words. He’d been thinking about getting the track down and spending the evening over at Folk City doing a guest set with Eric — his mind wired into the music. “What,” Floyd asked. “Hanged, what?”

“Childe hanged his self,” Dwain lifted his coke bottle, emphasizing “self.” They found him at his sisters or someplace on Long Island. Hanging from a tree or something. I heard it on the news and then some zombies at the Figuero leaned out the door and yelled it at me. “The gold coast king is dead. Sometime this morning or this afternoon.”

Floyd comprehended slowly at first. Childe. The guy they’d been following around? The famous folk singer down on his luck, who’d been with them at this very studio only a few days ago? The guy Floyd pestered for advice? The guy he knew from records, learning his licks as a kid. Dead by his own hand. Floyd finally got that while he tried to connect the bear who he’d last seen forlorn and foolish from these very steps, determined to get himself somewhere. At first he felt close to Childe, then far away. That was the guy, so that’s where he was going when they saw him walk up the stairs. Somehow it didn’t quite sink in. Floyd thought, maybe this is a joke or a dream. He’d had a plan for that guy. “I needed to learn something from him, and you tell me he’s dead. Killed himself.”

Floyd turned to the control room and shook his head. “Too much,” he said. “Too fucking much.” He walked into the booth dragging the heels of his cowboy boots and told the group.

“Yeah, sure,” Eric said.

“Man,” Ted said.

Heads shook.

Donnie the harmonica player, sat down. He put the harp to his lips and began to play a soft mournful tune. Everyone stood around. Hands in pockets, looking at their boots, drafted into their own thoughts.

They accomplished little more and when the session ended, Floyd choking on the stuffy studio air, cut away from the others. He stashed his guitar in the office, cut Dwain off sharply when asked where he might be going, and without knowing pumped his legs up the stairs. Running his hand along the carpeted walls he pushed through the metal door onto 8th Street next to the shoe store. A light rain danced across the puddles. He breathed the dank air and turned right, walking East in the early April evening. His neck felt stiff, almost glued in place. He tried cocking his head, and felt the snap of a wire pulled from its socket at the back of his brain. He moved his head right and left to get rid of the feeling. He hunched his shoulders and pulled up the collar of his pea coat.

He cut through Washington Sq. and walked downtown in the fog of his own drenched mind, twisting his head, trying to shake the loose wire feeling in his brain. His thoughts were not focused or coordinated, but resembled darts of light from a fireworks display. Flecks and smears lit through his imagination, small runner lights, stretched across his mind like creases in his forehead. His skin began to age as he walked, stretching across his brow and pulling his face taunt and ruddy in the wet air.

Maybe, Floyd thought, I can find some place to be close to him – a church maybe or a bench in some small park. “I think I had something to say to him, but I’m not sure,” he said to himself. The hot air from the studio still clogged his nose and he took deep breaths. He craved to be at some holy shrine where he could kneel. He kept walking, the evening fog floating on the rain coming and going through the streets and his mind, until a light dawned. I’m walking like this to get closer to Childe’s spirit, he told himself along his quickened pace; I need to ride out these straining chords in my stomach so I can breathe free.

Once he hit Houston, he felt better. From time to time he looked over his shoulder for Dwain, though he knew his friend wouldn’t be there. His thoughts simmered down to a hum. Songs threaded through his brain, “There you go, you and me” and Dwain singing, “Oh, mama, can this really be the end?” And then, “Here I sit in the ruins of your balcony.” “Don’t you – don’t you dare, don’t you dare draft me.” And here was Floyd marching, marching. A thunderbolt of destiny, unknown for his whole young life, struck a chord. Over and over the songs filtered though his brain, like light though a forest, jumping the synapses of their own accord, flying through his mind. Then, the words trickled out from all the lame music that Floyd had tried to write these past years, and he understood how the greats were the greats and he just didn’t have it and what did it matter anyway because we all had to die and did it matter whether we killed ourselves or whether someone else killed us in a foreign war or just keeled over from old-age? Did it matter? He was row, row, rowing his boat down the stream. He walked across Houston until he remembered his crazy drunken route with Dwain and headed over toward the Bridge. The wire in his brain, dangling and uncomfortable just minutes ago had been plugged back in. His head raced with thoughts, and his legs pumped. He lost his sense of time. The streetlights, the cars, trash in the gutter, shop windows, flashing neon; street signs became a blur. Motion speeded up and then slowed. The early evening darkness became dense and cloaked. The rain spattered on his chin. He felt confused and wished Dwain were with him. Then, he realized that the bridge where Dwain and he played at jumping off was the last time he had thought about death, and here he was again, powerless, frozen in the tracks of Childe who determined to leave the scene one way or the other – the gold coast king himself. He wandered along that side of town catching a glimpse of the lighted bridge.

He’d been kind of looking forward to the tall ships in spite of Eric’s cynicism. But, what’s to celebrate, Floyd wondered, walking and thinking, talking to a voice in his head. He’d spoken to Childe less than a dozen times and the coot hardly ever talked back, and when he did it never made sense. Why so upset? But Floyd knew Childe through his music, through his antics, through his own misery and depression and now finally through his death. So, he tried to think back to the last time he saw him, when Childe walked up the carpeted studio steps and looked at Floyd with that beatific smile ─ what’re you doing here? Aren’t you going to follow me all the way?

Floyd continued in a trance of his own devising, the hero of his own dreams transformed into bewildered human, step by step trampled by self doubt, by the fakery of his wild intentions, walking, suspecting what he could not do, but bluffing himself, daring himself, taunting, lacerating his mind with the torment of the left-behind, beating himself with false grief. He knew it would end soon one way or the other. Faking himself out, lying, coaxing and cajoling, outfoxing his jokey good for a laugh, good for nothing self, calling all his cards in, calling out the coward to come and save him now, the I don’t give a damn self, the brewery he’d made of his life, the attitudes of disdain, the impatience, the arrogance and self satisfaction of thinking he could do anything — reach up and pull down a god-damned great song from the heavens, something for keeps, he’d had it now, the thoughts, the schemes, the phoniness of standing on a stage and raising his voice while his insides screamed phony. All this was a stick stuck down his spine propelling him forward. He knew and he didn’t know. He cared and he didn’t care. He wanted and he disdained. He cried dry tears, certain knowing tears, fierce in the wind. Whichever way it turned out didn’t matter. Only the turning mattered. His earthly desires crouched behind his save the world performance. No more faking it by the rims of his eyes, the coaxing smiles and the pleasing good for nothing bow and scrape. Now he was on track. Now he knew he would do the right thing. His intentions propelled him. The moment would win and decide the triteness of his fate. This way or that perhaps according to a stray breath of wind. A hiccup. What was the use? No use. Son-of-a-bitch, Floyd turned out loyal; that’s all he had left.

By this time Floyd made it over to Centre Street. He headed along the walk fronting the buildings to the other side. The bridge full-scale in front of him. The screaming in his head died in the whirr of traffic. All that mattered seemed getting himself to the brink where he might feel some sense of decision along with a closeness to Childe. The wind stung his ears, the sky darkened; his pea coat lay wet and thin around his shoulders. The rain let up. He floated on the cold spring air as he walked on the side of the car lane, solemn in the melancholy of a new kindled purpose, scuffing his boots along the cast off road pebbles, out toward the middle. At this moment, he became driven by the wind at his back propelling him along the precarious curbed roadway next to the ribbed rail, the elegance of the bridge from far away, now ordinary and everyday up close. Even the metal spokes along the side were pitted and worn by weather. The bridge lights appeared without their sparkle. The startled clouds, covered and uncovered the tiny stars. He expected one of the cars to stop, but none did; their lights focused on the road as they sped past. Floyd went out where he gauged the middle, close to where he had stood with Dwain, where he looked south toward the ocean. Then he glanced left and right. He felt old and wise in the knowledge of this moment, cold, whipped by the breeze as he took in the giant city. Every building gleamed. The shine and luster shone through the night while Floyd shouldered his life heavy as a weight-bearing beam at the bottom of the bridge.

Floyd looked toward the mouth of the river where he could make out the dim horizon beyond another bridge through to the boundless beckoning sea, harboring ships come and gone with the days of old. He tried to picture anything to relieve the absolute truth that Childe went home and hanged himself. The stretched rawness opened the deep ravine to Floyd’s soul. Now he bunked on that same perch, willing to do anything to make the pain go away. Was this pain or numbness? He could not tell. Was this compunction? Was this destiny? Need he find the precise word? Need he name this thrust of his heart? Just this once, could he live without a word? He found nothing profound about the moment, a ringing in his ears that seemed always to have been there, carried on the flame of one moment lighting the next. Floyd’s young life crawled by, nothing more than a leaf about to fall. No redemption, no revelation, just a leaf falling on the water. How could this be?

A silent ship approached all in flames. Floyd could see the sails were full. Drawing closer, the ship glowed. The thin streamers from the highest topmasts sang in the wind. The ship plowed forward. Floyd could clearly make out the gun ports and the profile of Old Ironsides, defender of the Republic; the ship’s rigging strung intricate among the blaze. Scudding along the water, the burning ship glowed brighter. A mirage he thought. The ship crackled as it neared. Bring me to my senses, Lord.

He looked to see the fiery ship nearly upon him. Highlighted by the inferno, Floyd spied Childe’ bloated body hanging from the bowsprit, hands clutching at his neck, shrouded in the burning aura of that midnight sun. He remembered Childe from the studio steps – almost peace – no ambition, no recrimination, no mourning for what might have been.

Floyd leaned on the cold iron paling. The lower Manhattan skyline trimmed the western view. The night wind pulled. Shimmering clouds roiled the air. All this, Floyd thought. You can’t leave now. Looking down through the ties he saw the small white wave crests turn on the dark water. Grabbing the railing, in trembling union with the bridge, unprotected, urged by the wind, searching for a reason to live on, he folded to a crouch…with a pump of his legs and a vault over the side, falling on the rough air, sucked through his suffering into the sheltering arms, Floyd entered the deeps.