“A Friendship Thrives, With a Sack of Rice” by Nathaniel Spiller (Senegal)

A Friendship Thrives, With a Sack of Rice

by Nathaniel Spiller (Senegal 1970-72)

© 2008, The Washington Post/

reprinted with permission

•

Night falls quickly in Africa. Under a half-moon and partly cloudy sky, a single kerosene lantern silhouetted the contestants against the blackened backdrop. A boom box hooked up to a car battery played traditional Serer music, accompanied by drummers on plastic barrels. Thanks to word of mouth, and probably a few of the cellphones that are increasingly common in the bush, the Keur Waly N’Diaye wrestling tournament was about to begin in earnest.

On a day’s notice, several hundred people and maybe two dozen wrestlers from surrounding villages had arrived on foot or by cart and assembled in the open area between the hut-size mosque and general store. Bedecked with amulets and the occasional body paint, the young male hopefuls, all in their late teens or 20s, flexed and preened in skimpy loincloths. Meanwhile, the gathering crowd — women wearing colorful batiks and men in T-shirts and jeans — formed the three-deep perimeter of this impromptu arena.

Before the first bout, my son Dan and I had taken our spots in coveted ringside seats. For the next three hours, we would sit transfixed, honored guests at a sporting event that could have taken place two centuries ago.

All because of the $25 I spent on a 50-kilo bag of rice — the prize for the eventual champion.

A Father-Son Road Trip

For some time I dreamed of Senegal, and a return to the Peace Corps village I left in 1972. Ever since, I have kept up with the family who took me in when I was 21. In particular, I have kept up a correspondence with Biram N’Diaye, the village chief’s son — and now the village chief himself. Our special friendship began almost from the instant in 1970 when I was dropped off in Keur Waly N’Diaye, the tiny village that bears his father’s name.

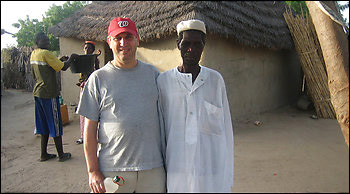

Nathaniel Spiller and Biram N’Diaye in 2006

Like most volunteers, I had several motives for joining: a desire to serve, to be sure, but also a desire to interrupt my academic studies and defer entering the “real” world by living someplace I might never otherwise see. The one place I did not want to see was Vietnam. I had signed up for the Peace Corps already, but then I drew #4 in the draft lottery, which meant I might soon be called up to serve in the war. That was the extra push I needed.

I arrived alone after three months of language, technical and cultural training at the village, which comprised about 10 families eking out a meager living growing peanuts, then Senegal’s primary cash crop. The families were extended and predominantly polygamous, and their separate compounds generally consisted of several huts organized around a central eating/sitting area and surrounded by a millet-stock fence. The more prosperous households — a category that did not include Chief Waly — lived in compounds that included a two-room cement-brick house with a metal roof. Yard space was shared with a variety of scrawny farm animals and a mangy dog or cat. There was no electricity or plumbing, not even outhouses.

It was an exceptionally small village for a Peace Corps posting, and my placement with the chief’s family as the village’s first and, to this day, only volunteer was unusually intimate. I naturally reached out to Biram, the chief’s eldest son, to mediate between me and other villagers, some of whom were skeptical of my intentions and capabilities. It was a role in which he excelled. At the time, Biram was 30, married and a father of four. Unlike many Senegalese, he spoke no French; in fact, as with the rest of the Keur Waly villagers, his primary language was not Wolof — Senegal’s most common — but Serer, a distinct tongue of his ethnic group and one that I never learned. A true peasant, he had no schooling and had never been out of the area; his one and only trip to the capital city of Dakar was to see me off when I was leaving.

In the years to come, I would return to Keur Waly several times, most recently in 1986 with my wife, nine months before Dan was born. But that was two children and more than 20 years ago. Meanwhile, Biram’s family had grown to nine children and numerous grandchildren.

Now I wanted to go back, this time with Dan, then a 19-year-old college sophomore. Any father-son road trip would have been great at this juncture in our lives, but I knew that Senegal, and especially the village, would be special. Having studied African development in school, Dan wondered “whether the poverty would be too sad to bear,” and what a country would be like where people earned less per year than he got in a month at a summer job. I wondered how it had changed.

Subsistence and More

Keur Waly N’Diaye is a four-hour drive from Dakar, if all goes well. To get there, we hired a taxi at Dakar’s sprawling intercity taxi depot. The farther inland we got, the hotter and drier it was; the heavily populated areas gave way to scattered villages of mud-brick huts and thatched or corrugated iron roofs. It was late May, a month before the start of the rainy season, and long stretches of farmland were desiccated and fallow. Cows, sheep and goats along — and sometimes on — the road looked emaciated.

Past Kaolack, 150 miles from Dakar, road conditions worsened dramatically. Unlike the well-paved Dakar-Kaolack road, this major route to Gambia was pitted with endless axle-eating potholes and shocks-rattling bumps. It was here that, within sight of the line of trees that marked Keur Waly, our car broke down. Despite the oppressive heat, we contemplated walking the last kilometer or so, dragging our suitcases behind us. Within minutes, however, a full seven-passenger taxi pulled up and crammed us in for the short ride to the village — no charge.

A cluster of folks was sitting by the road when we arrived, and we were immediately surrounded by men, women and children. Of course, Biram — older, grayer and walking with a profound limp caused by a horse cart accident some years back — was among them. The intervening years clearly told in his gaunt figure and lined face, but his familiar voice and grin were immensely reassuring. We embraced like the old friends we were and exchanged traditional Wolof greetings. Nanga def? How are you? Ana sa wah keur? How’s your family?

It felt natural to be there, the place where my mind often wanders when I’m sitting at my desk or jogging in Bethesda. Dan couldn’t help but notice how friendly and welcoming the villagers were; meanwhile, I surveyed the village for signs of progress or decline.

Today, Keur Waly is roughly the same size, inhabited by roughly the same families as when I first encountered it. There is a small convenience store, but still no electricity or plumbing. Water, always a problem, is even more so now — neither the well nor the cooperative vegetable garden, my main Peace Corps projects, lasted much beyond my tenure. Persistent drought and salt from the surrounding flats have made it difficult to maintain wells suitable for drinking or even irrigation.

People in this region always grew millet for their own consumption, but now they do so almost exclusively, having reverted to subsistence farming. And however monotonous a steady diet of that grain can get (it looks and tastes like wet sand), the villagers appear to be relatively healthy. Consequently, living to a ripe old age is not uncommon — amazingly, two of the original family heads I met decades ago are still alive, one of them 97.

Indeed, the village families made sure we ate quite well during our two days there, and not only because Biram had picked out a sizable rooster (dinner No. 1) and, at considerable sacrifice, bought a goat to be slaughtered (dinner No. 2). Lunch meant sitting around large, communal bowls of tieb-u-djinn (Senegal’s national dish of rice and fish) and digging in with one’s right hand.

Once fed, we sat in the shade of a cashew tree, surrounded by frolicking youngsters and adults conversing about family and friends, the weather and politics. A common theme was the hardship of village life, and Biram’s youngest son told of having risked a sea voyage to Spain, only to be deported for illegal entry. The children, however, were a happy lot. The older ones played marbles or chased each other around, while all it took was a stick and an empty plastic bottle to amuse a toddler pretending to be a truck driver.

At some point, in my fractured Wolof, I asked about wrestling, the country’s most popular sport. As I’d hoped, the men offered to organize a match for the last night of our visit if I would buy that bag of rice for the winner.

And so, Biram, Dan and I bused to the town of Kaolack, which in my Peace Corps days had had a certain sleepy appeal. I would go there regularly to get mail and a week’s worth of International Herald Tribunes, to use a real shower and to socialize at Peace Corps friends’ apartments. Now Kaolack had gone from being merely shabby to squalid. Considerably more populated, with garbage and filth overrunning the dusty, rundown streets leading to its vast market, it is a 21st-century version of Dante’s city of woe, encircled by its own fetid river and great wasteland.

We did our business quickly and returned to the village in time to witness the goat’s demise. Biram’s sons performed this deed with dispatch, slitting the animal’s throat and letting the blood drain into a sand pit, in accordance with Islamic law. Later, we would eat until we were stuffed.

In my contentment, I reflected on what draws me back to Keur Waly. Each time I’ve come for a different reason. Unchanging, however, has been my desire to see Biram and his family again, to re-experience village life for a short while, and to share with my traveling companions — Dan found it “incredibly serene and peaceful” — this place that has meant so much to me.

Pinned and Sacked

Ordinarily, wrestling matches are held past midnight, but Biram had decided this one would take place much earlier. By 8 o’clock, the young men, looking muscular and menacing, had arrived. The sun set and the proceedings began.

Each match started with the wrestlers facing off in a standing position. Typically, they were cautious at first, feeling each other out. Eventually there would be a quick move to grab a leg and the other man would countermove. Often they would both end up on the ground grappling one another, stirring up a cloud of dust and animal dung until the requisite pin suddenly happened and the referee ruled the fight over.

The first round lasted a long time, but after that the field narrowed quickly. Soon, it was down to two finalists. Dan was brought onto the field to take their picture. The championship bout followed the general pattern, starting slowly and ending in a violent flourish. When it was over, the crowd erupted in whoops and hollers, and the victor danced off with his ecstatic followers.

By then, it was past 11. The crowd promptly dispersed. Returning to our quarters, I missed seeing the winner get his prize but was told he had raised the heavy sack of rice triumphantly over his head, happy to go home to his village with bragging rights and enough to feed a large family for a month or more. Several villagers expressed their gratitude to me: Djirijef bu bah, bary-na neh ni trop. Thank you very much, the wrestling was really great. No doubt they will be talking about the Keur Waly tourney for many years to come. And so will Dan and I.

Leaving the next day, I vowed to return with my other son, bu sobe Yalla — God willing, as the Senegalese say.

•

Nathaniel Spiller is a retired government attorney and resident of North Chevy Chase, Maryland.

He returned to the village five year later (2012) for a similar visit (minus wrestling match) with his younger son. Biram was there to greet them, but died a few months later.

Very nice picture of what life in African villages revolves around. I could have substituted Chad for Senegal throughout and it would have rung true for me. Mr. Spiller, you are fortunate to be able to return to the site of your Peace Corps service. Chad continues in upheaval and I cannot risk a voyage back. But I can celebrate what you celebrate: how special serving was to each of us.

How exactly to promote business, affiliate marketer site, blog, social networking page up to 249605 active visitors each day

: http://usa.thebestseoservice.info/?p=37709